The Great Progression, 2025-2050

The time has come for a positive reframe of what’s really going on in America and the world right now, and what’s actually going to happen in the near future. For far too long we’ve been looking at our current situation and the coming decades through the lens of the past. Most people are stuck in the familiar default frame that sees many of our old systems breaking down in the face of myriad challenges like climate change, polarized politics, economic and social inequities, the paralysis of liberal democracies, and the rise of authoritarian states. That’s as far as they can see.

Yet we’re now at the point where we can view what’s happening, and what’s soon coming, through the lens of the future. That view sees the many nascent systems emerging that are superseding the old ones breaking down. This perspective sees many slow-moving positive developments coming to head, transformative technologies ready to scale, and new trends building to the tipping point. This perspective focuses not on breakdown but on rebirth.

So now there’s a new narrative able to come together about progress emerging all around us, about progress that’s inexorably coming as we lay the foundations for these new systems in the next 10 years, and about how they will scale in the next 25 years to help us solve many of the great challenges that appear to stymie us today. Let’s call this the story of The Great Progression.

This slow-moving, pro-progress story is being missed by most of the mainstream media chasing the minute-by-minute story of crisis and decline. Yet all the pieces of this positive story are now positioned to be catalyzed: There’s a loose pro-progress movement that’s emerging through different sectors of politics and the economy. There’s a new way of thinking about how to move American society, the Western world, and the world at large ahead. There’s also an emerging majority of smart, decent, and practical Americans who are realigning and getting positioned to make rapid progress in the years ahead.

This pro-progress story gets even better when you step back and think about the really big picture, when you think through how people living decades if not centuries from now will look back on our times. From that vantage point, we’re arguably at the beginning of a transformation that is going to change the world in profound and largely positive ways.

In the next 25 years, the world arguably will deal with climate change and transition the bulk of our core energy sources from carbon to clean. We will transition our transportation systems from the internal-combustion engine to electric mobility as part of an even larger process of reinventing cities. We will scale up brand new industries and build a much more environmentally and socially sustainable society. We very likely will reform capitalism around new economic priorities that counter the current imbalances and inequities. And we can be expected to revitalize our democracies and push back on authoritarianism around the world. People in 50, 100, or even 500 years from now may well look back on our era and marvel at the transformation that we’re about to go through.

“We’re arguably at the beginning of a transformation that is going to change the world in profound and largely positive ways.”

This is not just a nice utopian scenario, but a story of speculative journalism about what’s actually starting to happen, and most likely will play out over time. We’re up against world-historic challenges that require transformative and not just traditional solutions. America has pressed through historic junctures like this before, and we’re poised to do it once again. We need rapid progress along many fronts, and we are fully capable of meeting the moment this time too. We have mind-boggling new tools like artificial intelligence, and unprecedented knowledge like the ability to understand and engineer the genomes of all living things. The evidence and material for this extraordinary story is all around us.

This essay is going to lay out in broad strokes the world-historic story of the next 25 years of our lives. I’m going to explain the much more positive, pro-progress story of what lies just ahead. Hear me out because I’ve been through this drill before, 25 years ago, and that story proved to be very prescient.

The Long Boom Revisited

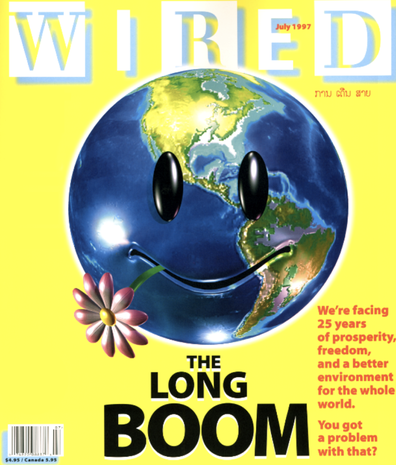

I worked with the founders of WIRED magazine in the mid-1990s, and we found ourselves in a situation that was very similar to today. We were at ground zero of the digital revolution and talking to many of the early technologists, entrepreneurs, and innovators who were super-excited about the progress being made with the new digital technologies — and beginning to see the vague outlines of what they could probably do in the coming decade, and what was possible to achieve in the next 25 years.

We at WIRED saw the need to articulate this future that was dawning on the early adopters but not seen by pretty much anyone else. I paired up with Peter Schwartz, one of the world’s premier futurists and co-founder of Global Business Network, a pioneering strategic foresight firm (where I also later worked). We co-authored The Long Boom, a History of the Future, 1980 to 2020, an iconic cover story for WIRED, which later became an influential book in multiple languages.

The Long Boom, in essence, was the pro-progress story of that time that helped catalyze the new zeitgeist of the 1990s with a positive reframe of what was actually happening. We took the historical perspective of how people in the future would explain the big-picture story of the 25 years that still lay ahead of us. We were about to go through two world-historic developments: the digital transformation and the integration of the world economy through globalization. But few really understood what we were heading into.

You must remember that in 1995 almost nobody knew what the digital revolution was, let alone what a digital transformation would be. There were only about 25 million people in the world on the internet, and most folks had no idea how these goofy startup companies with names like Amazon would ever amount to anything. Our story had to fill out the picture of how these technologies would scale, how these startups would grow, and how a digital economy would work.

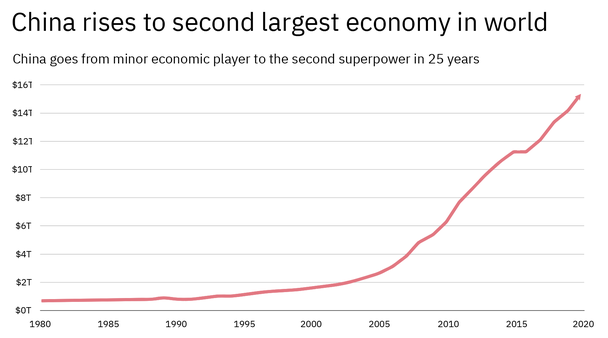

Likewise, in 1995 the Soviet Union had just recently fallen apart after 50 years of the Cold War, and the Chinese Communists were in the early stages of opening up to the market economy, with rural peasants starting to move to factories in cities. We had to explain how the global economy would morph into one integrated whole for the first time in history. We projected that we were about to head into a long digital tech boom, a long global economic boom — in other words, The Long Boom.

“The Long Boom, in essence, was the pro-progress story of that time that helped catalyze the new zeitgeist of the 1990s with a positive reframe of what was actually happening.”

How did we do? The broad-stroke through lines of that story pretty much played out by 2020. Those 25 million people on the internet grew to 4 billion, or 60 percent of all humans on the planet. The month our cover story came out, Apple begged Steve Jobs to come back as CEO because they were months from going bankrupt — yet Apple later became the first trillion-dollar company. China went from a middling country with less than $1 trillion GDP in 1995 to a superpower with a GDP of $15 trillion, pulling 800 million peasants out of extreme poverty. For that matter, the Dow Jones in 1995 was 5,000 but hit 30,000 by 2020. Another long boom, this time for stocks.

To be sure, we got some specific parts of that future story wrong, as can be expected. We thought we would have made more progress on climate change. We thought humans would make it to Mars by 2020, though that might take another decade or so. And we did lay out 10 possible negative developments that we were worried could disrupt or slow down the larger positive story we laid out. All 10 did actually appear in some form over the course of those 25 years (including a global pandemic), but the remarkable thing is that they still did not stop the overarching story.

What mattered was that The Long Boom helped distill at an early stage what would ultimately be seen as most important about our times in the long run of history. We roughed out the new models emerging in that first decade that were hard for people to imagine. We then helped project how those new models would scale up over 25 years and fundamentally change the world around us. We pulled off a positive reframe and helped people see the actual story of progress happening and about to happen in the decades ahead. Now it’s time to do something similar again.

The Positive Reframe of America Today

We’re living through an extraordinary time in American history, and really in all human history. Once you take that big-picture historical perspective, once you look at the whole forest rather than the individual trees, the real story of our times starts to make more sense. We happen to have arrived at a juncture between two very different historical eras and that makes everything on the ground very confusing, and very traumatic.

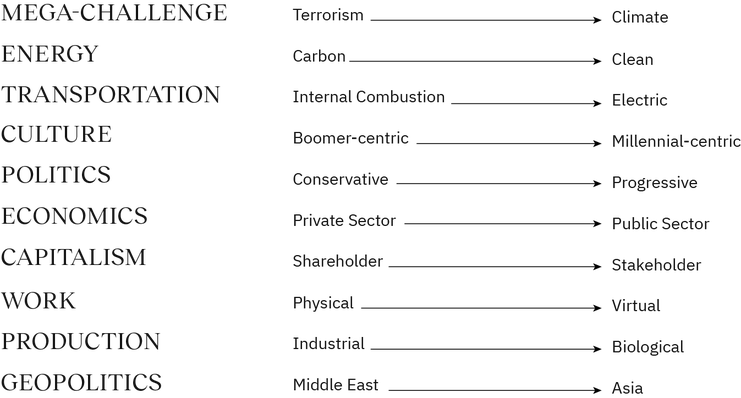

One way to understand this is that for the last 40 years America and the world have been operating within a series of interconnected systems that add up to one mega-system. Our energy system was rooted in carbon, and our transportation system was based on the internal combustion engine. Our culture was dominated by the huge Baby Boom generation and our politics tended to be more conservative. Our economics was all about unleashing the private sector and maximizing shareholder capitalism. Work was done in physical places and production was primarily industrial. Our uber-challenge was terrorism, and our geopolitical focus was the Middle East, which made sense because we needed to keep the carbon energy flowing to keep the whole flywheel of this mega-system spinning.

“We happen to have arrived at a juncture between two very different historical eras and that makes everything on the ground very confusing, and very traumatic.”

That whole mega-system, and all the subsystems, arguably are now breaking down and often causing more problems than they are solving. This world that older people spent their entire careers and lives mastering is coming to an end. This world that younger people were taught is “just the way things are” increasingly does not make sense. This world that politicians proudly had policies for, and that the media confidently analyzed and explained, is soon going to be over.

Every one of those systems arguably is being superseded by new systems much better suited for the 21st century. Our uber-challenge is now climate change and so our energy system must shift to clean power and our transportation system to electric. Our culture now is dominated by the huge Millennial generation and our politics are becoming more progressive. Our economics is raising the role of the public sector and capitalism being pushed to include all stakeholders. Work is now taking place much more virtually, and production is on the cusp of becoming biological. And our geopolitics is recentering on Asia, and in particular on the new superpower, China.

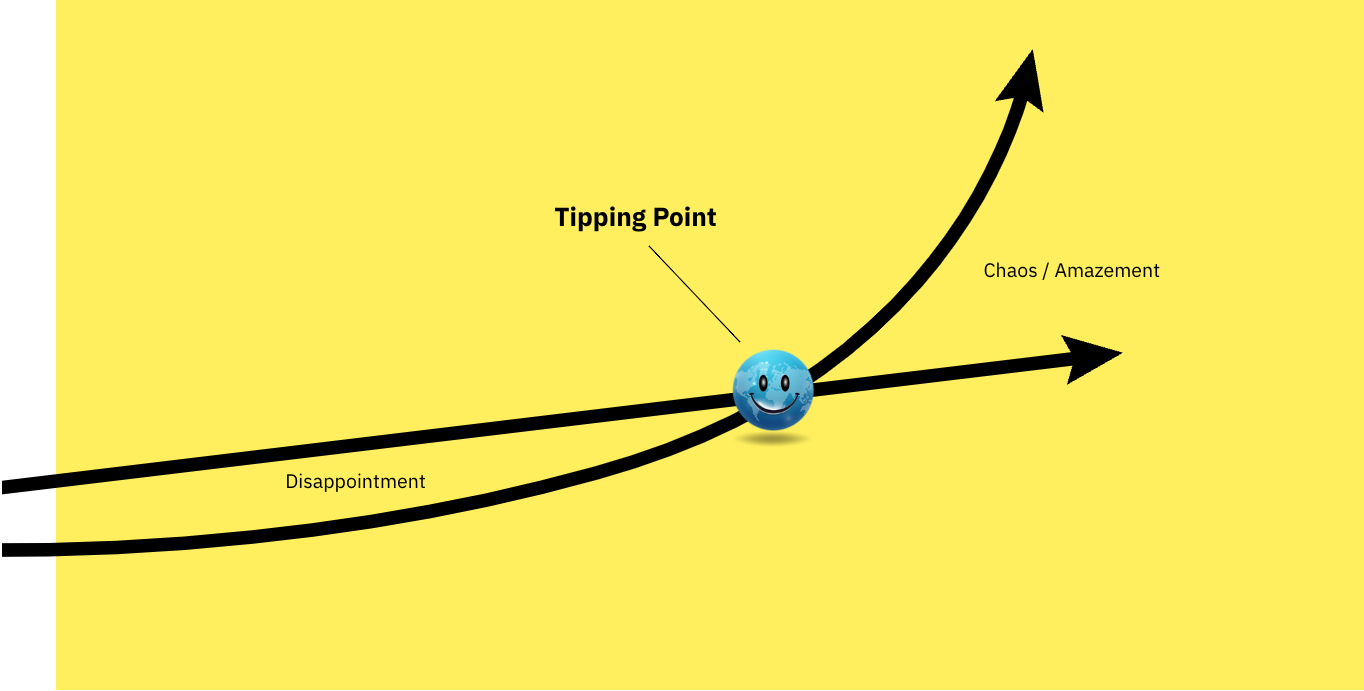

America and the world have been teetering on the tipping point between these two mega-systems for the last decade or so — but the absolutely critical point to understand is that we have now tipped. The shift is happening. The forces are in motion. There’s no turning back. There had been a debate, but that debate is now over. The transformation has begun.

Here’s the thing about tipping points: When they happen, they happen fast. This is a well understood phenomenon within the technology world. A new technology will slowly creep up in adoption until it reaches a tipping point — and then adoption will exponentially shoot up. The same phenomenon can be applied to trends and is used by the futures business. Some new trend will slowly grow in popularity on the fringes of society and once it gets enough exposure then — boom — everyone does it.

Here’s the other thing about tipping points: They prompt paradigm shifts in understanding what’s really happening and in strategy about what to do. One day the world works one way, like it always has, and then the next day it works a very different way. One day the world had a clear goal, a familiar one, and then the next day, there’s a very different goal. In other words, paradigm shifts set new north stars that rapidly reorient systems.

“Here’s the thing about tipping points: When they happen, they happen fast. … One day the world works one way, like it always has, and then the next day it works a very different way.”

Some of today’s tipping points — these system changes, these paradigm shifts — are easier to see than others. Take how all the debate and the efforts around climate change have tipped and are now sending out signals about this new north star. This summer’s so-called Inflation Reduction Act, which really is a $370 billion public commitment to accelerate the shift to clean energy and transportation, is only the latest signal to Americans and the world that this transformation has begun. Tesla had already led the entire legacy auto industry around the planet into an historic transition to electric transportation. And global finance had already tipped to massive investments into solar and wind power for utilities and away from coal because renewables are now cheaper — and getting cheaper by the year.

Or take the demographic tipping point between two huge generations that provide the cultural ballast of American society — that’s tipped too. The Boomer generation, now ages 58 to 77, is more than half into retirement and many are dying (the average lifespan of an American happens to be 77). The Boomers have been a highly individualistic generation in terms of culture, and the bulk of them were politically conservative from early on — contrary to the media portrayal of them in the 1960s. For every one of them out protesting on the left, there were two of them going off to war or getting ahead at work. Generations tend to form their political allegiances in their first several election cycles and hold those political values through their lives, contrary to the popular misconception that political values change in different stages of life. They usually don’t.

The Millennial Generation, now ages 26 to 41, are now all in the prime of their work and consumer lives. No wonder that corporate America has fully embraced Millennial values like diversity in their workforce and sustainability in their products and services. This shift makes even more sense when you factor in that Generation Z — now roughly considered ages 10 to 25, the bulk of them in high school or college — are remarkably aligned with Millennial values. The future in our culture and economy is getting clearer. All this will play out in our politics this decade, something I’ll come back to later.

The Next Long Boom, Squared

The original Long Boom story we told 25 years ago described the introduction of infotech, meaning digital computers and the internet, as a fundamentally new technology to the world stage. And then we described how it would scale up globally over the next 25 years and create a long tech boom and help drive a long economic boom, as well as a stock boom.

The next 25 years will see the introduction and scaling up of not one but three fundamentally new technologies that will have world-historic impact. One will be in energy tech, one will be in biotech, and one will be the next big stage of infotech, which will be driven by artificial intelligence. We’re heading into a triple-whammy tech boom — not just another Long Boom, but a Long Boom Squared.

“The next 25 years will see the introduction and scaling up of not one but three fundamentally new technologies that will have world-historic impact. We’re heading into a triple-whammy tech boom — not just another Long Boom, but a Long Boom Squared.”

Energy

The 2020s for energy tech will be a mad scramble to crack the new models. That energy tech world has tipped, the new north stars have been set, and the clear signals have been sent. We’re past that stage. Now the hard work begins on how to build out a clean energy infrastructure, a clean energy system. Humans have never done that before. A lot more solar energy, but where? A lot more wind, but how? And how does the grid need to adapt to these very different conditions? Who pays for the infrastructure, government or the private sector? The through line is clear, but not the specifics. We’ll get there through a churn of constant innovation and trial and error. It’s just not clear exactly how.

The scaling up of renewable energy, even at the most aggressive pace possible, won’t be enough to get off carbon energy in 25 years. We must have other forms of clean energy and so look to the development and deployment of next-generation nuclear energy. These small-scale nukes will be able to stabilize the grids of massive cities and keep CO2 out of the atmosphere. And they are far safer and the waste much less problematic than what people came to believe with the backlash from environmentalists in the 1970s. Even if we can get all our electrical grid on clean energy by 2050, it’s worth pointing out that some forms of carbon energy will still be needed off the grid, and we will probably need some fossil fuels indefinitely for other uses critical to our civilization, like ammonia.

The new models for electric mobility will follow a similar trajectory in the 2020s. The auto industry is clearly on its way with $350 billion in new private investment going into electric vehicles in 2021 alone. The charging infrastructure will need to be built, with a lot of prodding by governments and public investment. How do you charge private cars in dense cities? Millions of questions remain. But it’s all doable and will be done.

Biotech

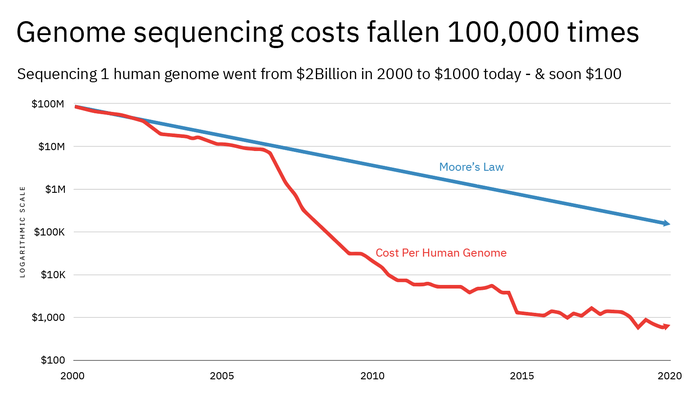

Then there’s the coming biotech boom. Most people totally underestimate the historical significance of very recent breakthroughs and great progress in this field. The first human genome was cracked only 20 years ago after 15 years of work at a cost of $2 billion. Today anyone can get their personal genome sequenced for $1,000 and in the next few years the process will cost $100. That is a mind-boggling pace of innovation that’s roughly twice as fast as what happened in infotech with Moore’s Law. Then 10 years ago we figured out how to cheaply and easily edit the genomes of living things with the breakthrough known as CRISPR.

The Biological Age has begun. If you can understand how genomes now work, and then are able to edit the configuration of those genes, then you have crossed the threshold into true genetic engineering. This means that we can now expand human engineering from the physical world of inert materials into the world of living things. But there’s even more to the story, thanks to recent breakthroughs not only in genetics, but also in many subfields of biology, like proteomics. We now understand how living things work below the cellular level, and we are getting better and better each year. We are expanding into a broader notion of not just genetic but biological engineering. This is what people mean by “synthetic biology.”

The new field of synthetic biology can be expected to play a big role in the next 25 years. Like many fields, it will be driven by climate change and the increasing need for sustainable everything. Climate change will probably force the use of much more genetic engineering applied to crops. We are used to hastening the genetic evolution of plants that we eat through classic cross-breeding, and we’ve seen the first wave of genetically modified crops. But we’ll almost certainly need to ramp up changes in most crops to become much more drought resistant, productive, and nutritious.

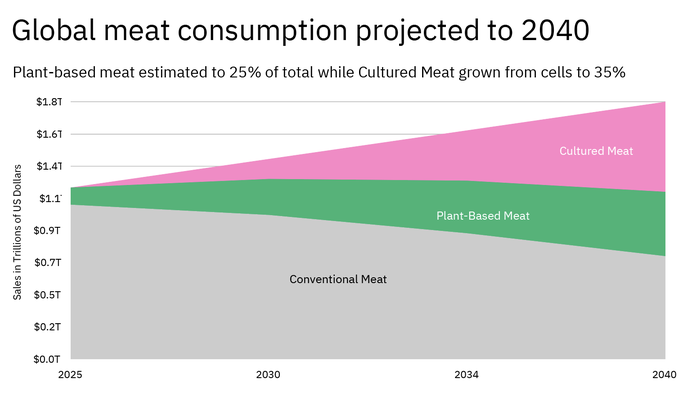

The sustainability imperative will probably also drive the dramatic expansion of biological engineering of “cultured meat.” This is the new technique where actual cells from a live animal can be replicated and grown as cultures in vats more efficiently than those cells can be grown within the animal on farms (and without the need for mass slaughter). Beef cells will almost certainly be the first to scale up because cows release methane and have a large impact on global warming.

“The new field of synthetic biology can be expected to play a big role in the next 25 years. Like many fields, it will be driven by climate change and the increasing need for sustainable everything.”

The bigger play for synthetic biology will be to take an increasing share of things that have traditionally been made through industrial production and make them through this new form of biological production. This moves synthetic biology into the world of materials. Building materials like steel and concrete account for a significant portion of CO2 that’s released into the atmosphere. Look for things like genetically engineered wood (stronger, heat resistant, faster growing) to replace them in an increasing share of structures — and suck carbon out of the atmosphere in the process. Or consider the plastics that are industrially produced from petroleum and then go into products like bottles and bags that litter our oceans and landscapes and only degrade after centuries. Biologically engineered alternatives could be designed to biodegrade within months after being exposed to salt water or extended sunlight.

Much of the action of the biotech boom in the next 25 years will take place in the world of human healthcare, and many of those implications on personal well-being and even life extension make many of today’s headlines. Synthetic biology is in the relatively early stages and so is developing largely under the radar so far. But that should change this decade and synthetic biology will be seen as a significant driver of the biotech boom, too.

Infotech

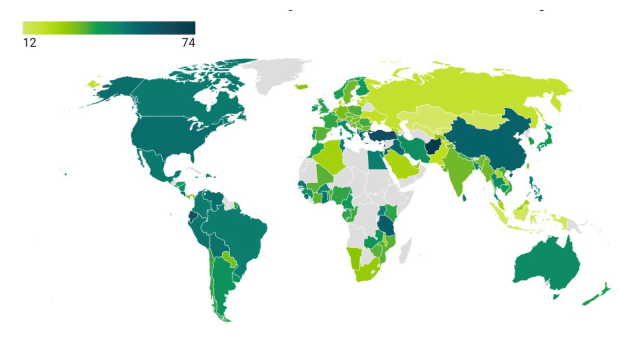

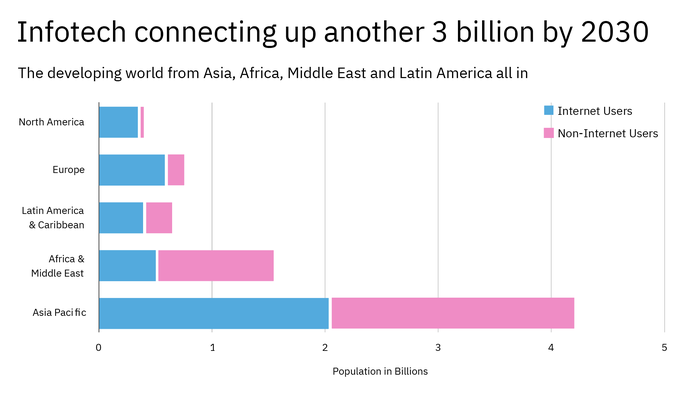

Finally, there’s the infotech boom, stage two. The first stage of infotech drove the last long boom but there’s plenty more action left in this field. For starters, the 2020s will see the addition of 3 billion more people who will get connected to the internet for the first time. New systems of low-level satellites will go fully operational and offer internet connections to all those who are still off the grid, which is still half of the population in Asia, two-thirds of Africa, and 40 percent of Latin America. By the end of this decade, the entire population of 8 billion people on the planet will be able to work or learn or shop online. This experience will be greatly enhanced by the buildout of the metaverse, the three-dimensional online world where people will be able to do more and more things in their lives.

The 2020s will also finish the digital transformation that most industries in the business world went through in the last 25 years. The world of government still has a long way to go on this relatively boring transformation, but the good news is the process will bring new efficiencies as well as new capabilities — as they did in business. And industries more entangled with the government and civic sectors, like education and healthcare, will finally go through the full digital transformation as well.

“The 2020s will see the addition of 3 billion more people who will get connected to the internet for the first time. … By the end of this decade the entire population of 8 billion people on the planet will be able to work or learn or shop online.”

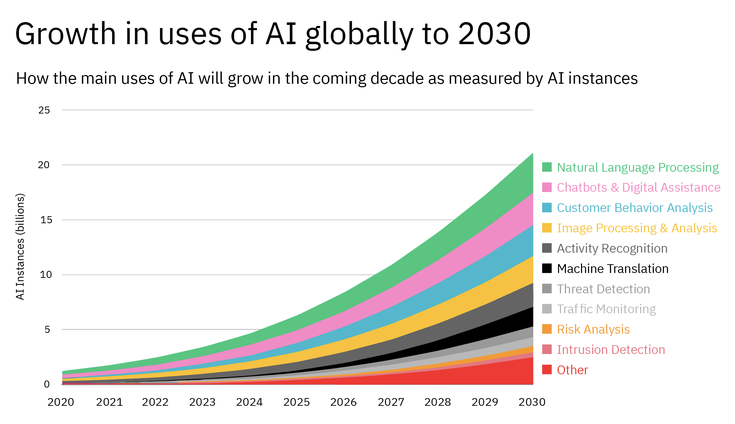

The new game-changer in this next stage of infotech is artificial intelligence. AI in the broad historical context gives humans a breakthrough superpower. Mechanical machines may have given humans the ability to dramatically enhance and extend our physical powers. AI will dramatically enhance and extend our mental powers. We will be able to let computers do things that in all previous eras required human intelligence, and more importantly, we will now be able to do things that human intelligence alone could never do.

This is a new, general-purpose technology that could eventually impact almost all fields over the next 25 years. Right now, we’ve seen early applications of machine learning pioneered by the big tech companies. (Ask any question and search all the information in the world to get an answer in less than a second. Wow. That’s something no human librarian could ever do.) The advanced business world has been applying the still relatively expensive techniques for the last decade to solve their problems. But over the course of the next 25 years AI will become increasingly simple, cheap and ubiquitous. Anyone will be able to take advantage of it through the cloud.

“Innovation essentially comes through the cross-fertilization of ideas and perspectives — and we are heading into a bonanza.”

AI is going to enable a mind-boggling amount of innovation. Take just the example of simultaneous language translation, something that AI will perfect this decade. Soon any person on the planet speaking any language will be able to fluidly communicate with any other person in real time, and with nuance, whether through video over the internet or with an earbud walking down the street. This opens up the world’s business and diplomatic conversation not just to the roughly half-billion native English speakers, or the highly educated bilingual elites of other cultures, but to every single human, regardless of culture or class. Innovation essentially comes through the cross-fertilization of ideas and perspectives — and we are heading into a bonanza.

The New Context of Abundance

Long booms often create the conditions for progress. They are usually driven by the introduction of fundamentally new technologies, which create new industries, which create new kinds of jobs, which create new wealth. If the new technologies are transformative enough, then they can take decades to scale and fully build out. And so over that same timeframe those new industries help drive a growing economy which leads to a more prosperous society. Booms tend to spread income and wealth around, which tends to make people less worried about their own prospects, more generous about sharing, and more open to change and progress.

Abundance is a big goal of every progressive era. Progressives want more of everything for everyone. Everyone should have a good job, good housing, good healthcare, good education, good opportunities, and good prospects. Everyone should be able to live a good life, not just the elites, or the top 10 percent of society, let alone the 1 percent. The good news is that many structural developments are aligning at this moment in history to create a different kind of 21st-century society of abundance. Let’s think through how the theme of abundance might play out the 25 years now opening up.

Abundance is the holy grail of the world of energy. The sophistication of all civilizations is essentially a function of how much energy they can use. The goal of our current shift to clean energies is not just to stop putting CO2 in the atmosphere, as important as that is, but to create a much better energy system that can provide cheaper, more abundant energy over the long term. Renewable energies like solar and wind are already getting cheaper than carbon energies, and they hold incredible potential to provide much of our energy needs. Still, they won’t get us far enough. There will be many other efforts to develop other kinds of cheap abundant energy, like new approaches to thermal energy, or fourth-generation nuclear energy.

“Long booms often create the conditions for progress. They are usually driven by the introduction of fundamentally new technologies, which create new industries, which create new kinds of jobs, which create new wealth. If the new technologies are transformative enough, then they can take decades to scale and fully build out.”

The potential game changer that could emerge is fusion energy, the promised land of nuclear energy. In contrast to conventional nuclear fission, which breaks down atoms to release energy, nuclear fusion “fuses” atoms together to create much more energy with no waste. We’re close to getting more energy out of these fusions than we put in, and we’ve seen a proliferation of fusion startups that are projecting that commercialization may be possible in the 2030s. If that happens, we might be able to achieve an unexpected energy abundance with widespread societal implications. For example, we might be able to rely on fusion for water desalination, which would require huge amounts of energy but could solve climate-related water shortages.

Abundant housing might be an unexpected outcome of game-changing innovations in transportation over this 25-year period. The lack of affordable housing is not just a problem of America’s big coastal cities, or now even just America. Almost every major city faces this problem — particularly the megacities of Asia. The one short reason is individual car ownership. Modern cities devote about one-third of all their real estate to cars. The bulk of that is for parking spaces in offices, or shopping malls, or driveways, or lining the streets. Most cars sit parked 95 percent of the time, totally unused.

Enter autonomous vehicles, which are just starting to be legally deployed in select cities like San Francisco. Expect autonomous vehicles to dramatically improve and scale up in our 25-year timeframe. One clear possibility is that autonomous vehicles will become a shared asset used by Millennials and Gen Z-ers who grew up sharing cars via Uber and the like. For the 5 percent of your life when you need a vehicle, you will summon one to your home or office (and maybe even jump in the driver’s seat if you want). When you are done, the vehicle will then go to the next person, and keep in circulation, only stopping to charge up. If this happens, then up to one-third of the real estate of cities could be repurposed for housing, making housing abundant, and therefore cheaper. This is not inevitable, but very promising.

Other increasingly costly expenses of modern American life might be poised for unexpected price drops in the next 25 years. Take healthcare, which the vast majority of Americans find way too expensive and so think of as scarce. The current healthcare system is a jerry-rigged monstrosity from the 20th century. But the next 25 years provide a potentially game-changing opportunity to redesign a 21st-century system using the new capabilities of genetic understanding and new tools of artificial intelligence. For example, knowing the genetic disposition of every individual or in some cases even tweaking that upfront could dramatically drop the costs of treating that individual downstream over his or her lifetime. Our increasingly nuanced understanding of the biology of the human body will inexorably lead to precision interventions that thwart illness and boost health — rather than our current relatively ignorant shotgun approach. The breakthrough approach of utilizing mRNA in developing vaccines during the pandemic gives just a taste of things to come.

AI also holds the promise of hyper-personalized medicine at scale over time. Your body will be constantly monitored through all your devices and even clothes and you could get a daily — not yearly — checkup by a qualified health professional that happens to be a machine. Expensive human doctors would only need to be called in for higher-level problem-solving. Cheaper, more abundant healthcare may truly be on the horizon.

Or take higher education, which has become prohibitively expensive. One of the main reasons is the mounting costs of human labor working in an ancient system that dates to medieval times. The institution has resisted almost any application of new technologies that have brought efficiencies and price reductions in other fields. The pandemic finally forced some tech adoption with interactive video, but much more needs to be done, and probably will with a more sophisticated metaverse that can truly scale the numbers of students to professors.

This is another area where the coming iterations of AI may be able to help provide more personalized learning that can match or complement the effectiveness of humans and help bring down costs. Teaching the basics, answering common questions, checking homework for routine progress could all be done by increasingly effective (and even personable) intelligent machines. That will leave humans to provide the critical and creative components of an education that will remain beyond machines, like mentoring, or inspiring, or socializing the next generation.

“The problem of the coming decades in America and throughout the aging West is going to be that there are not enough people to fill all the open jobs.”

But what about the loss of jobs! We spent the 2010s worried about how AI and robots were going to take away all the jobs. We’re going to spend the 2020s (and the next 25 years) thanking AI and robots for saving our asses and helping fill all the open jobs. This is the paradigm shift you need to go through when you cross over into boom times from bust times. The 2008 crash and the slow build out of the Great Recession put everyone in a mindset of scarcity. The long booms we’re heading into are more suited to a mindset of abundance.

Booms bring an abundance of jobs. The problem of the coming decades in America and throughout the aging West is going to be that there are not enough people to fill all the open jobs. We’re already getting a taste of this new reality in the wake of the pandemic. This will only get worse, with maybe a blip in a temporary forced pause in growth to get a handle on inflation, which is a symptom of booms rather than busts. We will need AI to help with these pressures. We will want robots to do much of the tedious and dangerous work. And, frankly, we can expect America to open immigration back up, too. We’ll soon welcome immigrants at the high end and the low end of the workforce. We’ll need everyone.

The New Progressive Era

The big-picture view of all American history shows some patterns that are useful when trying to figure out the future. One is a pendulum swing back and forth between conservative and progressive eras, between the alternating dominance of those on the right and the left of the political spectrum. This yin-yang of politics shows up in other Western democracies and can be seen as a reasonable way for societies to revitalize over time.

You can unpack the names themselves to understand the basic distinctions between the two approaches. “Conservatives” generally value “conserving” the traditional way of doing things, sticking to the tried-and-true ways that work — going back to basics. This tends to slow down changes and focus on consolidation and regeneration, which can be a good thing for societies at certain times.

On the other hand, “progressives” generally value “progress” or, more broadly, change. They are much more eager to experiment, try new approaches, and take risks. This makes them much better during transformative times when new systems are being built and no one really knows the clear way forward. They also value vigorous, effective government to force and guide changes. This approach also tends to open up opportunities and power to new actors, which benefits those on the bottom of the pyramid.

You can see this back-and-forth pendulum swing with even a cursory review of American history. Americans flat out named one period “The Progressive Era,” which marked an explosive period of reform at the beginning of the 20th century in reaction to the previous conservative era of the late 19th century that we remember as The Gilded Age of the Robber Barons. The most recent progressive era came off the Great Depression and World War II and ran through the post-war boom all the way through the 1960s. (That era’s progressives were labeled “liberals” for reasons specific to that time.) And then Ronald Reagan marked the beginning of the most recent conservative era, which I would argue came to an end with Donald Trump’s defeat in 2020.

What accounts for this pendulum shift between eras is a reconfiguration of the American electorate with a 60-percent majority coming together for a time on the center/right and defining the overarching terms of that era. And then that approach gets outmoded, and a different set of challenges emerges, and a different 60-percent majority forms on the center/left that drives the next era. The transition phase between eras, when the electorate is roughly split 50/50, is marked by extreme political polarization and governmental paralysis. That’s America in the last decade.

America in the 2020s arguably will be a very different place, and over the next 25 years will be in another progressive era. You can make the case for this by lining up the numbers of the growing constituencies that are coming together in the coalition behind Blue America and the Democrats. You can start with the double-barreled generations of Millennials and Gen Z who vote overwhelmingly Blue. Add to that the growing numbers of people of color, who are closing in on becoming the majority of all Americans as early as 2040. Add to that the college-educated and professionals who recently have shifted their support to the Democrats and are poised to grow their ranks as the knowledge economy burgeons in the years ahead.

You can see it in the polling on myriad issues. A solid 60 percent or often 70 percent or more of Americans now want to see progress, serious change, in many different areas. Their positions tend to line up more on the side of Blue America and the Democrats. They want progress on climate change, not climate denial, progress on income inequality, not just the freedom to get rich, progress on gender equality (and now protection of abortion rights), progress on racial issues, progress on gun violence. They also want progress on the affordability of housing, and education and health care for everyone. They want effective government that can get big things done. They want their democracy to work with everyone able to vote.

American politics has tipped. That’s the most dispassionate and realistic analysis of American politics right now to my mind. Watch this endgame play out in the next few election cycles. Unfortunately, the process might get very traumatic and possibly devolve into sporadic violence from time to time. This has happened in similar junctures between eras in American history, like during the 1850s and 1930s when Americans were on the cusp of transformative times. But America will get through this juncture and be on the move again. Just watch.

The Pro-Progress Realignment

There are two sides to all tipping points: a reaction away from what people don’t want or need anymore, and an attraction to what they do want or need. A core ballast of roughly 60 percent of Americans needs to also be attracted to the side of the political spectrum that seems most able to solve the current set of challenges, most in sync with the future. I’d argue that’s happening in America today with the emergence of what you could call a new kind of pro-progress movement or coalition that’s forming primarily in Blue America under the big umbrella of the Democratic party.

Democrats today often call themselves progressives but there is a lot of confusion about what being a progressive means. Let me wade into the mosh pit of Democratic politics and sort out what’s really going on. One big category are the progressives primarily looking backward: These are traditional progressives who still largely think in terms of 20th-century solutions. They love ideas like the Green New Deal or Medicare for All that in their very names are building off the past. Some of them are rooted in the labor movement that harkens back to the economic solutions of the 1940s and 1950s and are often anti-business. Others are rooted in academia and look back even farther, still calling themselves democratic socialists or even Marxists. Then there are “movement progressives” who are most concerned with identity politics and social issues around race and gender and gay rights and the like. They often default to adopting traditional progressive positions but are most focused on extending the rights movement that took off in the 1960s.

There’s now another growing category of progressives who primarily look forward: They are the ones figuring out 21st-century solutions. Because they are grappling with new solutions in real time, this category is harder to clearly define or even see. The best way to understand it is to watch what is going on in California today. The state of California is at the heart of the modernization of progressive Blue America right now. The Democrats in California have wiped out the Republican party from relevance starting about 15 years ago and they now have a wide-open field to try out big ideas about how to solve new 21st-century problems. They have super-majorities in both state houses. They hold all state-wide offices. And they have a visionary governor in Gavin Newsom.

Gavin Newsom comes much closer to embodying the new 21st-century progressive. He holds similar values to traditional progressives and appreciates the continued relevance of many of their preoccupations and concerns. But he is much more open to innovation and rethinking the path to progress on many different fronts. He’s also much more appreciative of the transformative power of new technologies and the value of entrepreneurship in dramatically changing the game. As the former mayor of San Francisco, Newsom gets the tech world, the innovation economy, and understands the incredible potential that’s now possible in the near future. Many California progressives do.

A key factor behind the tech world’s success is that it operates with a mindset of abundance, not scarcity. The digital economy of the last 25 years shows that the best way to succeed is not to make a scarce number of things and then charge top dollar for them. Much better is to figure out how to make vast numbers of abundant things and charge pennies, which add up to much more. The more you produce something, the more the costs drop. Ultimately, more people can afford to buy even more of those things, which lowers costs even more. Soon you enter the virtuous circle of economies of scale, with costs moving down and distribution going way up. Everyone benefits in a world of abundance — the consumers and the producers.

This abundance approach has worked really well in a world of easily replicable digital products like software, and it’s also now working in other physical tech fields, from solar panels to electric vehicles. Dramatically increase the supply to drop down the costs and you create a win-win world of abundance. And now this abundance approach is moving into progressive political thinking. Some are starting to talk in terms of “supply-side progressives” in distinction to traditional progressives. Or even “abundance progressives.”

Take the example of housing. A traditional approach on the left that saw the world in terms of scarcity would be to build public housing, or intervene in the market with rent controls in order to look out for working people. The supply-side approach goes: The problem with affordable housing is we need to dramatically increase the supply of housing to make it abundant, and therefore affordable. And so for the last five years the California legislature has passed a barrage of laws making it much easier to build homes, increase the supply, and drop the prices (which may take a decade to fully play out). They are doing this for the working people who need that housing, but the developers benefit too.

The mainstream California progressives like Newsom in that way are pro-business, pro-entrepreneur, pro-technology, pro-innovation — pro-progress. To be sure, they understand that tech companies that have exploded in size and other big businesses need a healthy counterbalance from government representing the interests of all people. But they appreciate the transformative power of these companies and these technologies, seeing them as essential to building the next generation of our economy and society.

California is still in the early stages of figuring out how to solve the many new challenges of the 21st century, and it’s far from perfect. Innovation is messy, with much trial and error. But California, more than any other state, is fully engaged in solving those future challenges, from climate change (now phasing out the sale of gas autos by 2035) to dealing with the diversity of its population (now only 35 percent white). California is the future when it comes to technology, the economy, society, and culture. It’s long played the role of prefacing America’s future.

California is the future of American politics too. The state has played that role on both sides of the political spectrum. Ronald Reagan honed his modern form of conservatism as governor of California 15 years before he became president. The 21st-century form of progressivism has been developing in California for the last 15 years and has been steadily moving out into blue states throughout the country, and even into the urban hubs of Red States. The 2020s will see it go fully national. We’ll soon see.

The Time for Grand Strategy

The America that could emerge in the next 25 years realistically could create the world of abundance described above. Abundant good jobs working in industries of the future that are on a mission to solve the big challenges of our time like climate change. Affordable housing in reinvented cities, affordable state-of-the-art healthcare, and affordable higher education for all family members to pursue the 21st-century American dream. When you create those conditions of abundance, you foster social cohesion rather than strife. You generate trust rather than cynicism. Rather than widespread pessimism, you get optimism again.

This is an America that is reminiscent of the burgeoning one of abundance that was built in the post-war boom of the 20th century, during that last era of great progress, our last progressive era. The people back then took their era’s relatively new technologies like the internal combustion engine and built out ambitious new infrastructures like the interstate highway system. They created a modern industrial economy that more broadly spread the ample wealth generated to benefit the majority of workers. They created a society of upward mobility through widespread public investment into higher education. To be sure, minority groups did not benefit from all this progress on an equal basis, but by the end of that era in the 1960s, the majority tried to rectify that too.

That post-war America not only worked internally but led the new way forward for the world in that transformative time of change. Our success in building new models that worked on the domestic front, after floundering as recently as the 1930s during the Great Depression, inspired others grappling with similar challenges in other parts of the world. We helped design and build the new international institutions of that time that were figuring out a new form of coordination between nations. And this revitalized democracy became the critical counterbalance to the world’s other option of that time: the authoritarian Soviet Union and communism. The resulting Cold War led to even more technical progress and social cohesion.

We’re in another one of those transformative times in history and there are many parallels we can learn from. A big one is that in transformative times you have to think in terms of what is called grand strategy, like they did back then. This is a game that is played another level up on the proverbial three-dimensional chess board. You must step back and think big-picture and long-term. You must clearly see what’s really happening, what’s probably coming, and what’s truly possible. You must think big and act bold. And you must take risks that meet the moment.

You have to think differently in transformative times because you are dealing with fundamentally new challenges like climate change, and you are designing new systems to cope with the new realities. That takes a different mindset of innovation and openness to change. The old ways don’t work anymore. The old strategies don’t apply because the game has changed. You’re playing a bigger game for much bigger stakes at the level of historic change. Even the old rules don’t necessarily apply. Never say never in these explosive periods of progress.

Transformative times of progress and system change also can bring a level of desperation because some people think in existential terms and can’t see beyond what they’re losing. Those rooted in the old systems often will desperately try to hold on because they clearly see what they will lose, and they can’t see what they ultimately stand to gain. This is one way to see the pervasive climate denial and delay tactics coming from the leaders in Red States with industries based on coal and oil. This is why we’re seeing increasingly apocalyptic talk of political violence and even civil war. America has seen that rhetoric before at similar junctures, and once even went well beyond talk.

America always gets through these high-stakes junctures, and we will do it again. We’ll do it in ways similar to what we have done in the past. The new pro-progress majority that forms on the other side will welcome people from both parties and be less partisan, less focused on what divided us in the past, and more focused on what unites us as Americans in the future.

Watch for progressive Republicans to start showing up. You can already see a young cohort of intellectuals in that camp who could be classified as pro-progress if not progressive. It’s worth a reminder that the Republican party began as the progressive force in America during the Civil War and drove transformative changes for decades afterwards. Republican Teddy Roosevelt kicked off The Progressive Era. Both American political parties always eventually adapt to the times and learn to play the new game in the new era. President Bill Clinton led the so-called New Democrats and largely played within the broader context of conservative politics that defined the recent era. President Dwight Eisenhower was a liberal Republican who did the same in the last progressive era.

Consider one final analogy to the past progressive era of the post-war boom: We may be heading into a new Cold War with China. The implications of transformative times do not stop at American borders but are convulsing throughout the world. When old systems start breaking down, and new systems are not yet fully formed, people all over the world desperately look for answers.

Authoritarian states provide a sense of certainty in the very uncertain times of transformation. Their centralized control of power allows them to act quickly and decisively compared to the messy processes of liberal democracies. (Even within liberal democracies authoritarian leaders and parties tend to thrive in these times.) China has been and will almost certainly continue to push big initiatives that will aggressively deal with climate change and other big challenges mounting in the world. China can be expected to showcase a model that will be attractive to developing nations and even any country that wants to emulate their success.

But Chinese President Xi Jinping is doing what almost every authoritarian regime and certainly every totalitarian regime ends up eventually doing. He is hanging onto power and getting the Chinese Communist Party to break with their tradition of rotating leadership at the top every 10 years. And as part of that process, he’s cracking down on all dissent, ramping up surveillance and social control, and fanning the flames of nationalism. The next decade is going to be a dangerous one.

The good news is that authoritarian closed societies always lose to open democracies in the long run — and this next 25 years should be no different. Historical periods of transformation and progress play to the strengths of societies that can correct course through frequent leadership changes. Open societies that encourage free thinking and are tolerant of dissent thrive in these periods dependent on widespread innovation. The process of democracies may be messy and relatively slow but in the long run they inexorably move forward and ultimately succeed. This happened in the last Cold War that ended in the collapse of the Soviet Union, and it most certainly will again if China gets increasingly totalitarian and mounts another Cold War.

One other bonus if a Cold War is forced on America and the West: External threats tend to accelerate social cohesion and progress. Serious external threats coming from a Cold War with a comparable power can be expected to bring Americans together behind a common purpose again and thrust us back into global leadership. A Cold War can be the rationale for channeling massive amounts of resources into research, science, new technologies, new infrastructure, and expanded education — all the elements that historically have led to more progress. An undesirable and unwanted Cold War could be yet another historical development that supercharges The Great Progression.

The Moment is Now

We’re living through an extraordinary moment in the history of America and the world, one that will be remembered for a long time to come. In the next 25 years humans are going to figure out how to significantly slow global warming, adapt our economies and societies to the changes already baked in, and prepare for more to come.

To do that, humans are going to have to work at a planetary scale with a level of global coordination that we have never done before. We may have to pull off that global effort with two competing coalitions of democratic and authoritarian states. Hopefully we will have a more seamless evolution of global governance with all peoples of the world reasonably getting along and staying roughly aligned.

We’re going to have to leverage the full capabilities of advanced technologies in three fields that will have world-historic repercussions. In infotech we’re going to get all 8 billion people on the planet connected and eventually connect literally trillions of things. We’re going to need to take advantage of the full superpowers of artificial intelligence and advanced robotics helping humans do things that we alone could never do.

In biotech we’re going to master genetic engineering and even the much broader biological engineering in order to redesign as many products and materials and foods as necessary to be fully sustainable and more closely in sync with nature, meaning low-impact and biodegradable. We’re going to jumpstart the new industries of synthetic biology and begin in earnest the Biological Age.

And in energy tech, of course, we’re going to do something that’s never been done: Transition as many people as possible as fast as we can from one foundational source of energy based in carbon to an array of energies that will from now on be clean. Part of that world-historic effort may be to finally cross the threshold of nuclear fusion and harness the energy that powers the sun and all stars.

In the next 25 years humans will have crossed several fundamental thresholds that presumably any sufficiently intelligent species on other planets in the universe only cross once. We will be well on our way to being sustainable, living within the environmental bounds of the planet, with many more challenges ahead. We will have learned to operate in much more sophisticated ways at a global level on a planetary scale, with much more to come.

This epic story is starting to unfold around us today. The demographic shifts, the cultural changes, the economic evolutions, even the counter-intuitive political breakthroughs — the whole transformation has begun. The bulk of everything laid out here is the probable through line of what will happen over the next 25 years. Like any informed look into the future, not all elements will follow the first-pass trajectory across the next 25 years that I laid out here. But most seem likely to play out.

This generally positive, pro-progress story is actually much more likely than the current conventional wisdom — from the right or left, from the vast majority of media or academics — that says we’re caught in an unfolding disaster and heading into a dystopian future. The gloom-and-doom naysayers have always been the main chorus in previous times of transformation, and so far, they have almost always been proven wrong in the long run. They will be proven wrong again.

Do not fall for the inevitable setbacks to this generally positive, pro-progress story. For every two steps forward, there will be one step back. And sometimes there will be two or three steps back before we move forward again. This is the way progress works; this is the way history works. The dotcom crash did not stop The Long Boom, as critics were quick to pronounce, but marked a pause, and some rethinks in strategy, before the digital transformation inexorably picked up again. The same will happen this time, so don’t just focus on the exact outcome of this year’s midterm election, for example, or whatever else might temporarily counter this narrative. Keep your eye on the horizon. Keep thinking long-term.

All that said, The Great Progression is not inevitable. We will have to make this, or something roughly like this, actually happen. This pro-progress narrative of the next 25 years is certainly possible, and arguably is even probable, but what really matters is whether enough people see it as preferable. You can start with a clear vision, but you need to then shift to broad strategies, and then detailed plans. We must make it so.

Humans at this juncture in history have everything we need to pull this off. We have developed amazingly powerful tools that can look back through vast distances in space and see what happened at the beginning of time, 13 billion years ago. We have greatly expanded the reach of knowledge in every imaginable field, including how our own brains work. And now we have designed thinking machines that can help us learn even faster and know far more.

Never bet against human ingenuity. Human beings are incredible problem-solvers. We’ve gotten particularly good at problem-solving over the last couple centuries, and the pace of innovation has only been building decade after decade, year after year. Our tools keep getting better and better. Our knowledge keeps inexorably expanding in every direction. We are steadily mastering the game of progress. We might be up against some complex challenges, but we have all the capability we need to pull off another leap forward in progress.

We may not yet see what’s really happening around us now, and what actually will happen in the next 25 years. But people in the future, and maybe for a long time into the future, will look back and fully appreciate what we are about to accomplish. People in 100 years, or 500 years, or even 1,000 years from now, will look back on our era and credit us with several world historic accomplishments.

They’ll say: That’s when the world went fully digital, that’s when the world became mostly sustainable, that’s when the world started working on a truly planetary scale. What an amazing time that must have been to live through The Great Progression.

* * *

Top 10 Spoilers

The Great Progression, the largely positive story of the next 25 years, may be probable but can’t be considered inevitable. There are many potential negative developments that could emerge to slow down or thwart progress in solving the great challenges of our time.

Here are my own top 10 worries about what could stifle the great progress that lies just ahead:

Liberal Democracies Fail — America and liberal democracies around the world need structural reforms to effectively carry out the actual will of their majorities and be able to more rapidly adapt to the big changes in the 21st century. They might not.

Quasi Civil War — Zealots on the American far Right get so desperate that talk of civil war crosses over to actual political violence in a country armed to the teeth with guns. Containing such civil unrest could seriously set us back.

Enforced Group Think — Zealots on the American far Left take cancel culture to the next level and truly stifle open debate and free thinking in universities and other public forums, with the whole of pluralistic society suffering.

Losing Track of Truth — Facts continue to get more and more contested until people can’t communicate across parallel universes of media. Many of the fundamental pillars of advanced societies, like science, get jeopardized.

Tech Gets Demonized — The dramatic success of tech companies in the last 25 years has made them new targets for misplaced scapegoating. We will need an array of new technologies and vibrant tech companies to help solve the challenges ahead. We can’t demonize or undermine them too much.

Genetics Gets Shut Down — We will need synthetic biology and the whole new world of biological engineering to help create sustainable everything and solve climate change. Fears about messing with Mother Nature or God could shut those efforts down.

Nuclear Bomb Explodes — We’ve managed to avoid a nuclear explosion since Nagasaki, but nuclear proliferation continues. All it might take is an actual nuclear bomb going off to shut down the entire nuclear energy industry again and cut off the promise of nuclear fusion. We’ll need both this century.

Desperate Oil States — The rapid shift from carbon to clean energy could make the world’s oil states increasingly desperate and lead to unpredictable gambles, particularly with a fading power like Russia.

Balkanized World — There’s no way to solve climate change without the whole world evolving in common directions, and this gets much more complicated if globalization reverses and devolves towards uncoordinated localities. Let’s hope we don’t get more virulent global pandemics.

China Hot War — The world arguably could survive and possibly even thrive from a competitive Cold War between China and America, but an actual hot war between these superpowers would be catastrophic. It’s not impossible.