What counts as consciousness?

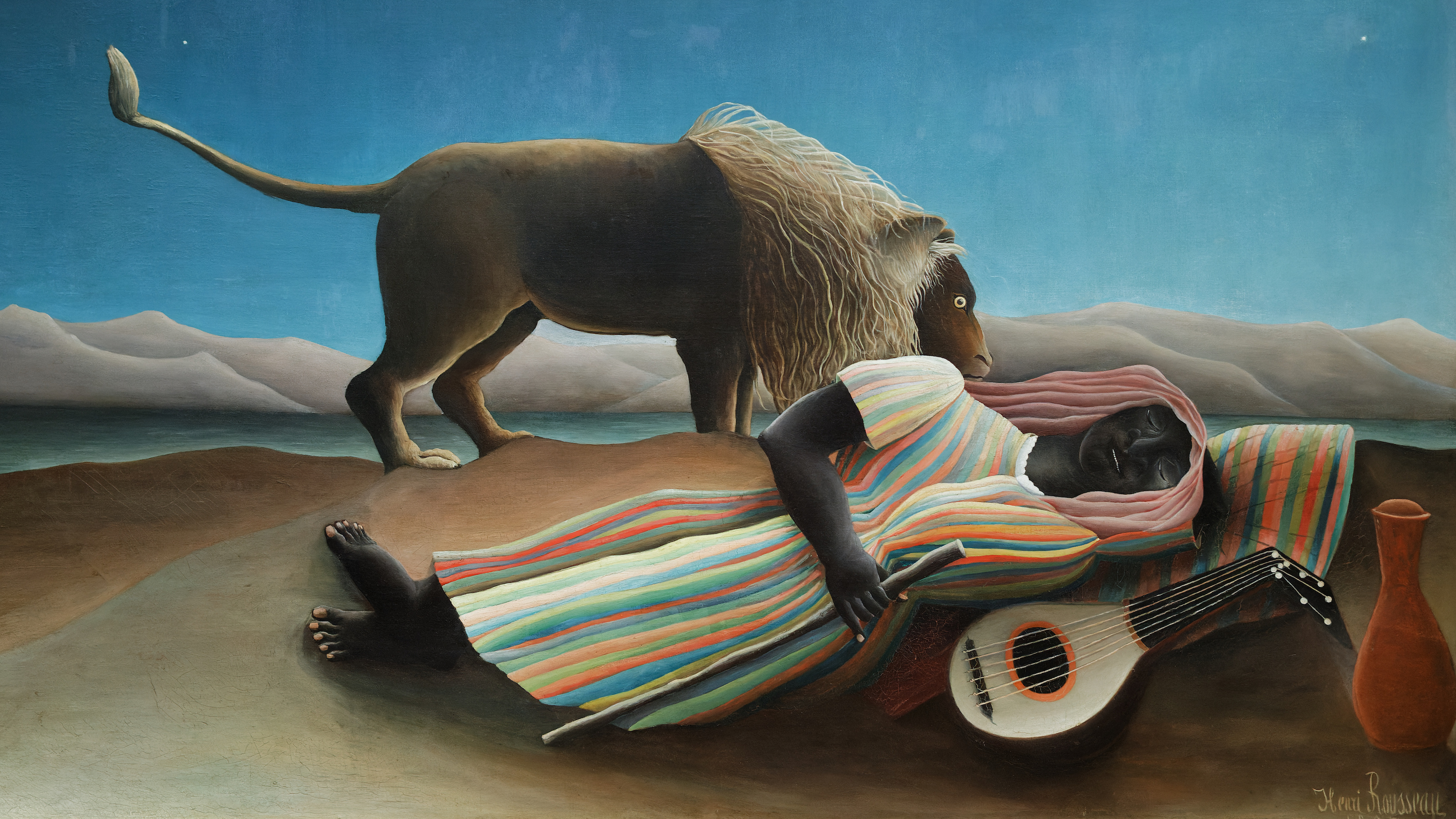

Some years ago, when he was still living in southern California, neuroscientist Christof Koch drank a bottle of Barolo wine while watching The Highlander, and then, at midnight, ran up to the summit of Mount Wilson, the 5,710-foot peak that looms over Los Angeles.

After an hour of “stumbling around with my headlamp and becoming nauseated,” as he later described the incident, he realized the nighttime adventure was probably not a smart idea, and climbed back down, though not before shouting into the darkness the last line of William Ernest Henley’s 1875 poem “Invictus”: “I am the master of my fate / I am the captain of my soul.”

Koch, who first rose to prominence for his collaborative work with the late Nobel Laureate Francis Crick, is hardly the only scientist to ponder the nature of the self—but he is perhaps the most adventurous, both in body and mind. He sees consciousness as the central mystery of our universe, and is willing to explore any reasonable idea in the search for an explanation.

Over the years, Koch has toyed with a wide array of ideas, some of them distinctly speculative—like the idea that the Internet might become conscious, for example, or that with sufficient technology, multiple brains could be fused together, linking their accompanying minds along the way. (And yet, he does have his limits: He’s deeply skeptical both of the idea that we can “upload” our minds and of the “simulation hypothesis.”)

In his new book, Then I Am Myself The World, Koch, currently the chief scientist at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, ventures through the challenging landscape of integrated information theory (IIT), a framework that attempts to compute the amount of consciousness in a system based on the degree to which information is networked. Along the way, he struggles with what may be the most difficult question of all: How do our thoughts—seemingly ethereal and without mass or any other physical properties—have real-world consequences? We caught up with him recently over Zoom.

In your new book, you ask how the mind can influence matter. Are we any closer to answering that question today than when Descartes posited it nearly four centuries ago?

Let’s step back. Western philosophy of mind revolves around two poles, the physical and the mental—think of them like the north and the south pole. There’s materialism, which is now known as physicalism, which says that only physical really exists, and there is no mental; it’s all an illusion, like Daniel Dennett and others have said.

Then there’s idealism, which is now enjoying a mini-renaissance, but by and large has not been popular in the 20th and early 21st century, which says that everything fundamentally is a manifestation of the mental.

Then there is classical dualism, which says, well, there’s clearly physical matter and there’s the mental, and they somehow have to interact. It’s been challenging to understand how the mental interacts with the physical—that’s known as the causation problem.

And then there are other things like panpsychism, that’s now becoming very popular again, which is a very ancient faith. It says that fundamentally everything is “ensouled”—that everything, even elementary particles, feel a little bit like something.

All of these different positions have problems. Physicalism remains a dominant philosophy, particularly in Western philosophy departments and big tech. Physicalism says that everything fundamentally is physical, and you can simulate it—this is called “computational functionalism.” The problem is that, so far, people have been unable to explain consciousness, because it’s so different from the physical.

What does integrated information theory say about consciousness?

IIT says, fundamentally, what exists is consciousness. And consciousness is the only thing that exists for itself. You are conscious. Tonight, you’re going to go into a deep sleep at some point, and then you’re not conscious anymore; then you do not exist for yourself. Your body and your brain still have an existence for others—I can see your body there—but you don’t exist for yourself. So only consciousness exists for itself; that’s absolute existence. Everything else is derivative.

It says consciousness ultimately is causal power upon itself—the ability to make a difference. And now you’re looking for a substrate—like a brain or computer CPU or anything. Then the theory says, whatever your conscious experience is—what it feels like to see red, or to smell Limburger cheese, or to have a particular type of toothache—maps one-to-one onto this structure, this form, this causal relationship. It’s not a process. It’s not a computation. It’s very different from all other theories.

When you use this term “causal powers,” how is it different from an ordinary cause-and-effect chain of events? Like if you’re playing billiards, you hit the cue ball, and the cue ball hits the eight ball …

It’s nothing woo-woo. It’s the ability of a system, let’s say a billiard ball, to make a difference. In other words, if it gets hit by another ball, it moves, and that has an effect in the world.

And IIT says you have a system—a bunch of wires or neurons—and it’s the extent to which they have causal power upon themselves. You’re always looking for the maximum causal power that the system can have on itself. That is ultimately what consciousness is. It’s something very concrete. If you give me a mathematical description of a system, I can compute it, it’s not some ethereal thing.

So it can be objectively measured from the outside?

That’s correct.

But of course there was the letter last year that was signed by 124 scientists claiming that integrated information theory is pseudoscience, partly on the grounds, they said, that it isn’t testable.

Many years ago, I organized a meeting in Seattle, where we came together and planned an “adversarial collaboration.” It was specifically focused on consciousness. The idea was: Let’s take two theories of consciousness—in this case, integrated information theory versus the other dominant one, global neuronal workspace theory. Let’s get people in a room to discuss—yes, they might disagree on many things—but can we agree on an experiment that can simultaneously test predictions from the two theories, and where we agree ahead of time, in writing: If the outcome is A it supports theory A; if it’s B, it supports theory B? It involved 14 different labs.

The experiments were trying to predict where the “neural footprints of consciousness,” crudely speaking, are. Are they in the back of the brain, as integrated information theory asserts, or in the front of the brain, as global neuronal workspace asserts? And the outcome was very clear—two of the three experiments were clearly against the prefrontal cortex and in favor of the neural footprint of conscious being in the back.

It’s not my brain that sees; it’s consciousness that sees.

This provoked an intense backlash in the form of this letter, where it was claimed the theory is untestable, which I think is just baloney. And then, of course, there was blowback against the blowback, because people said, wait, IIT may be wrong—the theory is certainly very different from the dominant ideology—but it’s certainly a scientific theory; it makes some very precise predictions.

But it has a different metaphysics. And people don’t like this.

Most people today believe that if you can simulate something, that’s all you need to do. If a computer can simulate the human brain, then of course [the simulation is] going to be conscious. And LLMs—sooner or later [in the functionalist view] they’re going to be conscious—it’s just a question of, is it conscious today, or do you need some more clever algorithm?

IIT says, no, it’s not about simulating; it’s not about doing—it’s ultimately about being, and for that, really, you have to look at the hardware in order to say whether it’s conscious or not.

Does IIT involve a commitment to panpsychism?

It’s not panpsychism. Panpsychism says, “this table is conscious” or “this fork is conscious.” Panpsychism says, fundamentally, everything is imbued with both physical properties as well as mental properties. So an atom has both mental and physical properties.

IIT says, no, that’s certainly not true. Only things that have causal power upon themselves [are conscious]—this table doesn’t have any causal power upon itself; it just doesn’t do anything, it just sits there.

But it shares some intuitions [with panpsychism]—in particular, that consciousness is on a gradient, and that maybe even a comparatively simple system, like a bacterium—already a bacterium contains a billion proteins, [there’s] immense causal interaction—it may well be that this little bacterium feels a little bit like something. Nothing like us, or even the consciousness of a dog. And when it dies, let’s say, when you’re given antibiotics and its membrane dissolves, then it doesn’t feel like anything anymore.

A scientific theory has to rest on its on its predictive power. And if the predictive power says, yes, consciousness is much wider than we think—it’s not only us and maybe the great apes; maybe it’s throughout the animal kingdom, maybe throughout the tree of life—well, then, so be it.

Toward the end of the book, you write, “I decide, not my neurons.” I can’t help thinking that that’s two ways of saying the same thing—on the macro level it’s “me,” but on the micro level, it’s my neurons. Or am I missing something?

Yeah, it’s a subtle difference. What truly exists for itself is your consciousness. When you’re unconscious, as in a deep sleep on anesthesia, you don’t exist for yourself anymore, and you’re unable to make any decisions. And so what truly exists is consciousness, and that’s where the true action happens.

I actually see you on the screen, there are lights in the image; inside my brain, I can assure you, there are no lights, it’s totally dark. My brain is just in a goo. So it’s not my brain that sees; it’s consciousness that sees. It’s not my brain that makes a decision, it’s my consciousness that makes a decision. They’re not the same.

You can simulate a rainstorm, but it never gets wet inside the computer.

For as long as we’ve had computers, people have argued about whether the brain is an information processor of some kind. You’ve argued that it isn’t. From that perspective, I’m guessing you don’t think large language models have causal powers.

Correct. In fact, I can pretty confidently make the following statement: There’s no Turing test for consciousness, according to IIT, because it’s not about a function; it’s all about this causal structure. So you actually have to look at the CPU or the chip—whatever does the computation. You have to look at that level: What’s the causal power?

Now you can of course simulate perfectly well a human brain doing everything a human brain can do—there’s no problem conceptually, at least. And of course, a computer simulation will one day say, “I’m conscious,” like many large language models do, unless they have guardrails where they explicitly tell you “Oh no, I’m just an LLM—I’m not conscious,” because they don’t want to scare the public.

But that’s all simulation; that’s not actually being conscious. Just like you can simulate a rainstorm, but it never gets wet inside the computer, funnily enough, even though it simulated a rainstorm. You can solve Einstein’s equation of general relativity for a black hole, but you never have to be afraid that you’re going to be sucked into your computer simulation. Why not? If it really computes gravity, then shouldn’t spacetime bend around my computer and suck me, and the computer, in? No, because it’s a simulation. That’s the difference between the real and the simulated. The simulated doesn’t have the same causal powers as the real.

So unless you build a machine in the image of a human brain—let’s say using neuromorphic engineering, possibly using quantum computers—with that, you can get human-level consciousness. If you just build them like we build them right now, where one transistor talks to two or three other transistors—that’s radically different from the connectivity of the human brain—you’ll never get consciousness. So I can confidently say that although LLMs very soon will be able to do everything we can do, and probably faster and better than we can do, they will never be conscious.

So in this view, it’s not “like anything” to be a large language model, whereas it might be like something to be a mouse or a lizard, for example?

Correct. It is like something to be a mouse. It’s not like anything to be an LLM—although the LLM is vastly more intelligent, in any technical sense, than the mouse.

Yet somewhat ironically, the LLM can say “Hello there, I’m conscious,” which the mouse cannot do.

That’s why it’s so seductive, because it can speak to us, and express itself very eloquently. But it’s a gigantic vampire—it sucks up all of human creativity, throws it into its network, and then spits it out again. There’s no one home there. It doesn’t feel like anything to be an LLM.

This article originally appeared on Nautilus, a science and culture magazine for curious readers. Sign up for the Nautilus newsletter.