The brain’s “switch” that puts fear into overdrive

- Fear is crucial for survival, but an inappropriate fear response causes anxiety disorders and conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Recent research identified the molecular mechanisms underlying inappropriate fear.

- The findings could eventually lead to treatments for anxiety disorders and PTSD.

Fear is essential for survival, serving the important evolutionary purpose of increasing an organism’s vigilance and alerting it to dangerous and potentially life-threatening situations. An inappropriate fear response can, however, be harmful. Such responses are triggered in the absence of any real threat and play a role in a variety of anxiety disorders, as well as in conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Fear occurs in response to certain environmental cues or in specific contexts. Inappropriate responses can occur when fear generalizes to other situations, but we still know very little about the neural mechanisms underlying these processes. Recent research published in the journal Science now provides fresh insights into the molecular mechanisms by which the brain turns stress into fear, suggesting ways in which inappropriate fear responses could be prevented.

The generalized fear response

To investigate, Huiquan Li of the University of California San Diego and her colleagues induced a conditioned fear response in mice by placing them in a cage and repeatedly administering mild electric shocks to their feet. The animals learned to associate that particular environment with the shocks, and they showed fear, as measured by “freezing” behavior when placed back in that same environment two weeks later.

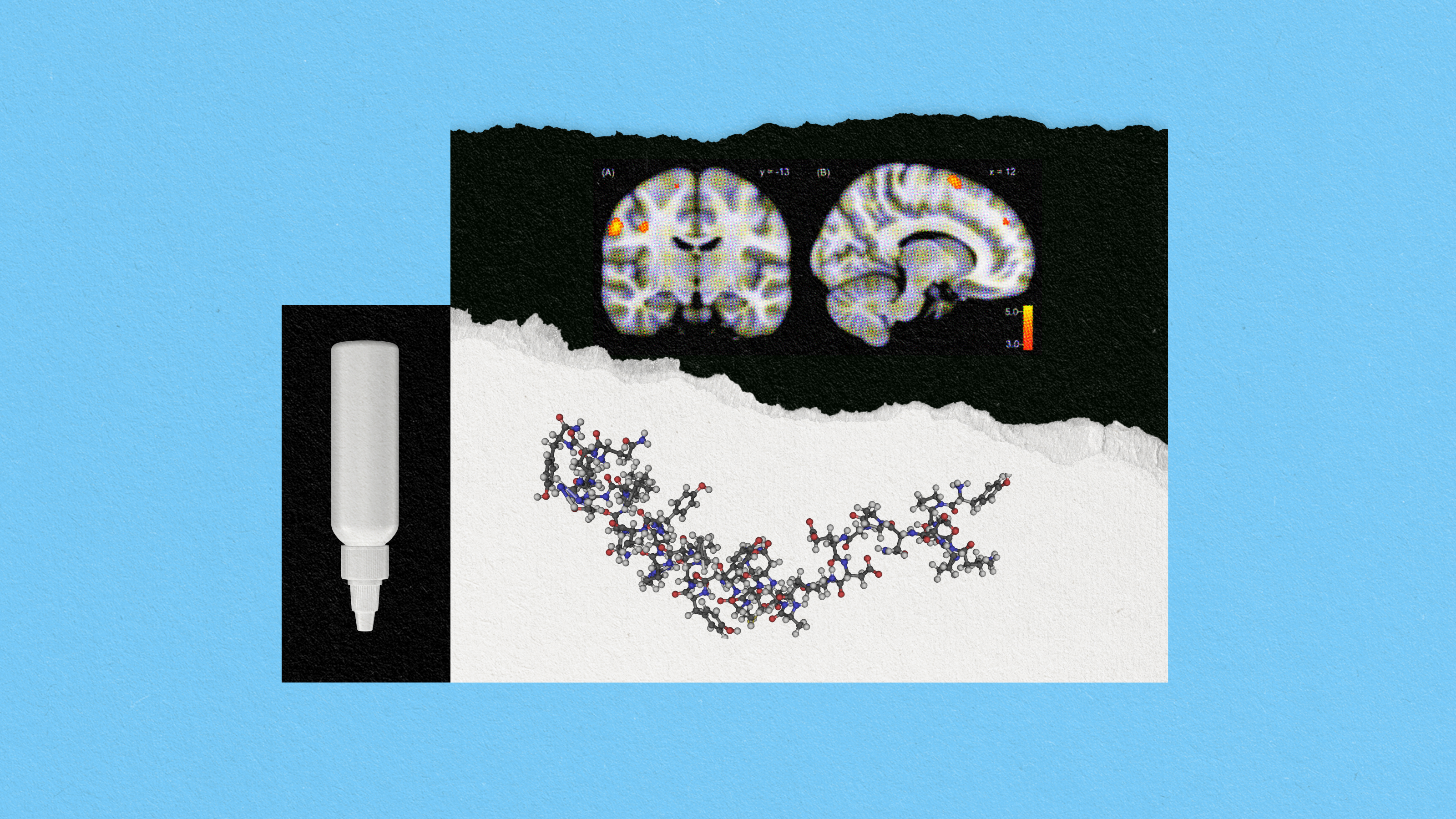

When the mice were given larger electric shocks, their fear response generalized to other contexts, such that they froze when placed in cages of different shapes, sizes, colors, and textures. After researchers examined the brains of these mice, they found that the generalized fear response is associated with a chemical “switch” in a part of the brainstem called the dorsal raphe nucleus, whereby neurons stop releasing the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and release the inhibitory transmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) instead.

These switching neurons send fibers up to other brain structures called the amygdala and hypothalamus and regulate the generalized fear response, which could be prevented by blocking GABA synthesis in these cells.

A path toward interventions

The researchers also found that treating the mice with the antidepressant fluoxetine (Prozac) immediately after giving them electric shocks blocked the neurotransmitter switch and prevented the generalized fear response.

Finally, the researchers performed post-mortem examinations of the brains of people who had been diagnosed with PTSD, finding the same neurotransmitter switch in the dorsal raphe nucleus.

“The benefit of understanding these processes at this level of molecular detail — what is going on and where it’s going on — allows an intervention that is specific to the mechanism that drives related disorders,” said senior author Nicholas Spitzer in a statement. “Now that we have a handle on the core of the mechanism by which stress-induced fear happens and the circuitry that implements this fear, interventions can be targeted and specific.”