The hornet has landed: Scientists combat new honeybee killer in US

In early August 2023, a beekeeper near the port of Savannah, Georgia, noticed some odd activity around his hives. Something was hunting his honeybees. It was a flying insect bigger than a yellowjacket, mostly black with bright yellow legs. The creature would hover at the hive entrance, capture a honeybee in flight and butcher it before darting off with the bee’s thorax, the meatiest bit.

“He’d only been keeping bees since March … but he knew enough to know that something wasn’t right with this thing,” says Lewis Bartlett, an evolutionary ecologist and honeybee expert at the University of Georgia, who helped to investigate. Bartlett had seen these honeybee hunters before, during his PhD studies in England a decade earlier. The dreaded yellow-legged hornet had arrived in North America.

With origins in Afghanistan, eastern China and Indonesia, the yellow-legged hornet, Vespa velutina, has expanded during the last two decades into South Korea, Japan and Europe. When the hornet invades new territory, it preys on honeybees, bumblebees and other vulnerable insects. One yellow-legged hornet can kill up to dozens of honeybees in a single day. It can decimate colonies through intimidation by deterring honeybees from foraging. “They’re not to be messed with,” says honeybee researcher Gard Otis, professor emeritus at the University of Guelph in Canada.

The yellow-legged hornet is so destructive that it was the first insect to land on the European Union’s blacklist of invasive species. In Portugal, honey production in some regions of the country has slumped by more than 35 percent since the hornet’s arrival. French beekeepers have reported 30 percent to 80 percent of honeybee colonies exterminated in some locales, costing the French economy an estimated $33 million annually.

All that destruction may be linked to a single, multi-mated queen that arrived at the port of Bordeaux, France, in a shipment of bonsai pots from China before 2004. During her first spring, she established a nest, reared workers and laid eggs. By fall, hundreds of new mated queens likely exited and found overwintering sites, restarting the cycle in the spring. The hornet’s fortitude — it is the Diana Nyad of invasive social wasps — allowed it to surge across France’s borders into Spain, Portugal, Italy, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Switzerland in only two decades, hurtling onward by as much as 100 kilometers a year.

Suspected stowaway

As the hornet fanned out across Europe, scientists in North America wondered when it might arrive on their side of the Atlantic. Queens sometimes overwinter in crates and containers, allowing them to stow away on ships and be transported long distances. In 2013, researchers cautioned that a yellow-legged hornet invasion at any one point along the US East Coast would have the potential to spread across the country.

After the first sighting last summer, Georgia’s agricultural commissioner urged people to report hornets and nests, and warned that the yellow-legged hornet could threaten the state’s $73-billion agriculture industry. American farmers grow more than 100 different crops, including apples, blueberries and watermelons, that depend on pollinators. Georgia mass-produces honeybees and ships them north to jumpstart spring crops, like Maine blueberries, before local pollinators have awakened.

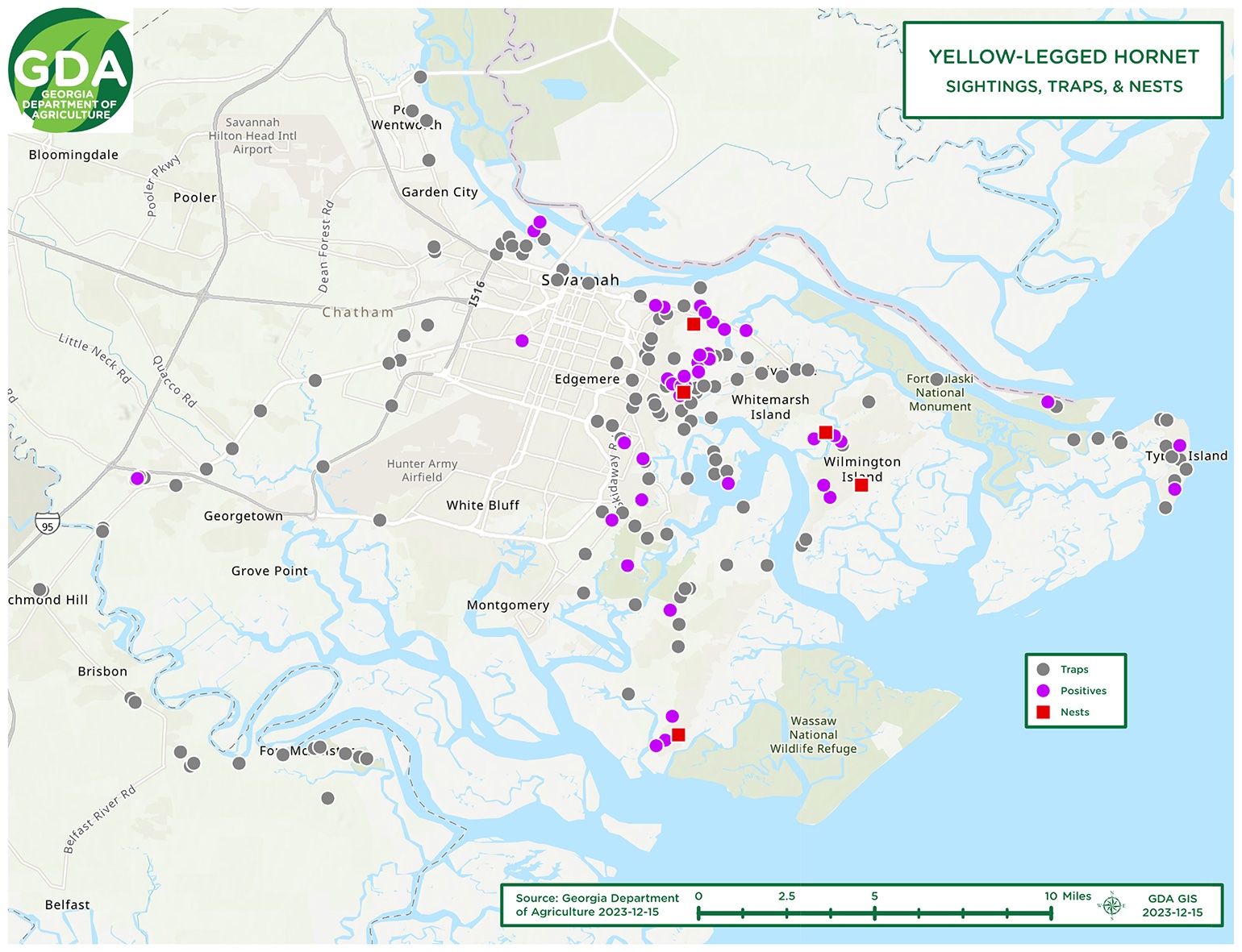

Less than two weeks after the first hornet was spotted, scientists found a nest in a tree, 25 meters off the ground. In a night operation, while the hornets idled, a tree surgeon climbed to the nest, sprayed it with insecticide, and cut it down. Just a quarter of the full nest was the size of a human torso, and the Georgia Department of Agriculture displayed a chunk, still wrapped around the branch, at a press conference — warning that this was larger than those seen in Europe.

“Savannah, Georgia, is primo climate for these guys,” says Otis. It’s a lush, subtropical paradise, giving the insect a long growing season — and a rich hunting ground.

For the next several months, Bartlett helped the state agricultural researchers set traps and follow individual hornets to find other nests. By the end of 2023, they’d removed four more. “We think we’ve discovered them at a very early stage, which is why pursuing eradication is very, very plausible,” Bartlett said in November. If not, Georgia and its neighbors could get caught in an endless — and costly — game of whack-a-mole.

Social wasps: Invasive global predators

The yellow-legged hornet and other social wasps, like the common yellowjacket, the German yellowjacket and the western yellowjacket, have successfully invaded every continent except Antarctica. They’ve been introduced to new areas by global trade, sometimes more than once over several decades.

The hornets live in colonies of individuals organized into groups that divvy up the labor of reproduction, foraging and caregiving. These behaviors, and the insects’ nearly omnivorous appetites, make them among the most successful invaders of new habitats and fiercest aggressors of native fauna. In their endemic ranges, these wasps are eaten by skunks, squirrels or bears, or snagged in flight by kingbirds and tanagers, or attacked by other predatory wasps. But in the absence of predators, their toll can be enormous.

In New Zealand’s Nelson Lakes National Park, the beech forests are thick with invasive yellowjackets by early autumn. They sip the sugary secretions of scale insects living on the trees, and will fight the bellbirds, tui, silvereyes and other birds for it, even slaughtering nest-bound chicks. The densities of the yellowjacket nests — up to 40 nests per hectare and 370 wasps per square-meter of tree trunk — are among the world’s highest.

“When you walk through the forest, you should smell the sweetness of the honeydew and hear the birds,” says invasive species biologist Phil Lester of Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, coauthor of a review of management strategies for invasive social wasps in the 2019 Annual Review of Entomology. “But with the wasp, you don’t hear the birdsong, you don’t smell the honeydew.”

In Hawaii, the western yellowjacket has had dramatic impacts on the island ecosystem. Genetic studies show that the original population came from the Pacific Northwest or Northern California, possibly in a shipment of Christmas trees. It hunts native bees and drains the nectar from the wispy red flowers of the ‘ōhi’a lehua tree, stealing food from other pollinators and curtailing seed production.

“They eat everything,” says ecologist Erin Wilson-Rankin of the University of California, Riverside, who has been studying invasive social wasps for nearly 20 years. “They don’t specialize. They’ll eat caterpillars, aphids, flies, the whole gamut of arthropods.”

Controversial tools

People have tried just about everything to get rid of wasps: fire, boiling water, electricity, traps, poison and brute force. While many poisons do work, they can also harm native insects and other animals. New Zealand has suppressed yellowjacket populations in highly trafficked areas with a selective poison bait called Vespex, but they reinvade elsewhere.

Nest destruction can kill hundreds of wasps at once, but it’s dangerous: Yellowjackets can squirt venom into an attacker’s eyes, and stings can be painful or life-threatening. Reiner Jahn, a hornet-buster and research assistant for a local landscape conservation association in Germany, describes the pain of a yellow-legged hornet sting as “digging a hot rusty knife into your flesh.”

Another approach to managing invasive species is biological control: A different species, often a natural enemy, is transplanted into the ecosystem to take on the role of contract killer. It can do the trick, but the long history of this strategy going awry (think harlequin ladybirds, cannibal snails, small Asian mongoose, cane toads) gives pause.

Cajoling foreign predators to take root in new places is another bother. In New Zealand, for example, the government recently approved the release of a non-native hoverfly and beetle to target invasive wasps. In Europe, both species hitch a ride into the hornet nests, feasting on the juvenile hornet grubs and decimating the next generation. But the imported insect predators had to have their seasonal cycles flipped before they could be released in the Southern Hemisphere. After some setbacks, scientists released about 20 hoverflies into the wild on the northern end of the South Island in mid-May.

Lester has other ideas: Silencing some of the wasps’ essential genes could reverse their spread. A handful of genetic control technologies are being tested globally to target invasive or harmful insects. For example, the biotechnology company Oxitec aims to combat the spread of dengue and other mosquito-borne diseases by releasing gene-edited male mosquitoes that produce female offspring that die young. (It’s the females that bite and spread disease.) Other researchers are using CRISPR gene editing on a range of agricultural pests to reduce pesticide use and save crops.

In 2020, an international group of researchers, including Lester and Wilson-Rankin, sequenced the genomes of three invasive social wasps: the common yellowjacket, the German yellowjacket and the western yellowjacket. Lester then zeroed in on a gene called ocnus that’s involved in sperm development, with the goal of making sterile males.

Like many insect pests, common yellowjackets are haplodiploid, which means that fertilized eggs become female wasps (with two copies of each chromosome) and unfertilized eggs produce males (with only one copy of each chromosome). If a queen mates with a sterile male, the eggs laid would produce only male wasps. Without female worker wasps, the nest would fail. But Lester’s modeling has shown that it would take decades for the mutation to spread across the South Island wasp population. So he continues to look for new genetic targets that might snuff out New Zealand’s invasive wasps more quickly.

Many people are unsettled by the idea of releasing genetically modified organisms into the wild, even if it’s to save native species, but the approach carries advantages. The impact would be precise; it wouldn’t poison other animals or insects. It would disperse over large distances and into remote areas. It would also be self-perpetuating, so people wouldn’t have to climb long ladders in protective suits to cut down enormous nests full of angry wasps.

Nest busting

On a hot afternoon in mid-September, Jahn, the German hornet-buster, pulls up to the Metropolitan International School in Viernheim, an industrial town east of the Rhine River. Kids run and jump in the playground, until a teacher ushers them away. High in a tree overhanging the soccer field is a caramel-colored, beach-ball-sized yellow-legged hornet’s nest.

“The kids can’t play soccer. I had to close the field because it is too dangerous,” says Oliver Wagner, the school’s facility manager.

A whiff of revenge hangs in the air as Jahn and his crew set up. Each is a beekeeper who has lost colonies to yellow-legged hornets, or knows someone who has. Jahn extends a telescopic pole fitted with a spray nozzle into the branches. He jabs the nest and blows in a fine powder called diatomaceous earth as chunks of the nest tumble to the ground. Hornets stream out like the air escaping from a punctured balloon.

Dusted with the white powder and unable to fly, the inch-long yellow-legged hornets wander through the grass and across the tarp. The crew picks through the nest debris and they tweeze the larger hornets into specimen bottles. When a nest is attacked — whether by a predator or a human — the queen may try to escape, Jahn explains. Find her, and the work is done. This time, she’s unaccounted for.

The trick to stopping a yellow-legged hornet invasion is to find the nests and destroy them before hundreds of new queens fly out in the fall to establish their own nests. EU member states must, by law, control the hornet’s spread, but Germany has strict rules that protect pollinator and native insects and limit what beekeepers and hornet-busters can do. Diatomaceous earth, often used in homes to kill cockroaches and centipedes, has become Jahn’s go-to solution. It sticks to the hornet’s exoskeletons and dries them out but doesn’t spread to other insects.

In all of 2023, Jahn destroyed 160 yellow-legged hornet’s nests in his home state of Hesse and 80 in a neighboring state, most brought to his attention by beekeepers. After a few years of nest-busting, he’s given up beekeeping (there’s no more time) and he no longer believes that the yellow-legged hornet can be eradicated in Germany — the country may have waited too long to start removing nests. Still, he says, “it’s easier to do something now than wait until next year.” But by mid-May this year, he’d already fielded calls for 19 new nests, compared with only two by late May last year.

Back in Georgia, Bartlett has tracked down the source of the captured yellow-legged hornets. His genetic analysis shows that a single queen arrived from southern China, the Korean peninsula or Japan in late 2022. He believes the hornets captured last year were the first American-born generation founded by the stowaway queen. Now, the second-generation has emerged. “We have been finding queens a little further out than we had hoped. But nothing near the distances they see in Europe,” says Bartlett. As of the end of April, the state had trapped and destroyed 21 queens.

Bartlett sees the work as his duty to protect the beekeeping industry, but his hope is that the hornet won’t define his scientific career. Still, he knows he can’t relent. “If we don’t get rid of them, there is very little chance that I’m not going to become the yellow-legged hornet expert in the US.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.