You face 60 “Choice Points” each day — and they define who you are

- A “Choice Point” — that critical moment you decide to accept or decline a challenge — has the power to define who you are.

- We may face up to 60 Choice Points per day, and our decisions often default to an arm wrestle with willpower.

- Tools like FIT (Functional Imagery Training) provide the agency to manage those decisions, increasing confidence and performance.

Imagine your alarm sounds on an early January morning. You wake and look outside. It’s cold and raining. Even though you’ve been diligent to your internal commitment and have every intention to get healthy, you decide not to go out for a run. You think, tomorrow will be drier. You go back to your cozy bed and snooze for an extra 30 minutes. Finally you get up, and you feel guilty, which depletes your drive and derails your hopes for a healthier start to the year. Feeling slightly ashamed, you decide to have a big breakfast to cheer yourself up. You then realize that the same thing happened yesterday and the day before that. You think, maybe I’ll try again in February. This is the Choice Point: To run or not to run? That is the question.

Truth is, we ask ourselves “to-do” or “not-to-do” questions every day, then make key decisions that influence our behavior moving forward. Choice Points usually happen when we face a challenge. They pop up during (or right before not doing) an infinite variety of activities: office work, writing a thesis, preparing for an exam, running up a hill, swimming the last mile, or working through a challenging dynamic in a relationship. For each of us, a Choice Point decision has the power to define who we are: a runner/nonrunner, an academic/nonacademic, healthy/not healthy.

By the time you get to a Choice Point, usually you have already invested a great deal of energy, emotion, and attention and made many personal sacrifices that have you in a state of feeling depleted or a loss of motivation. When you feel drained, negative thoughts rush forward in open rebellion, and the challenges can seem insurmountable. This is the moment you need to make a critical decision that will reveal aspects of your character — your mental toughness and grit. We experience about 6,000 to 60,000 thoughts per day. To understand that you are free to choose which of these thoughts you act on can change your life and has the potential to shape your destiny. Yet our decisions often default to the question of willpower because, at that critical Choice Point, we forget to ask ourselves why we want to do the action and what it means for our future.

The Choice Point is a moment that offers two options: mental mutiny or cognitive control. While mental mutiny threatens to lead us to disappointment in our actions, cognitive control is the antithesis, rooted in a commitment to our long-term goals, values, and meaning.

In a day, even if only 0.1% of the 60,000 thoughts you have are Choice Point moments, that amounts to 60 critical “yes or no,” “stop or go,” “quit or continue” opportunities to choose. The Choice Point is not unconscious; it involves conscious thought. Thus, you have the agency to manage those thoughts as they enter your consciousness rather than default to an arm wrestle with willpower that you might lose due to mental fatigue.

Still, we have found that by teaching our research participants and our clients to manage their attention during specific times of the day by perceiving obstacles and planning next steps through imagery, they report stronger willpower and a greater sense of free will, which increases their confidence and performance.

If personal health is so important to us, why do we struggle to follow through with decisions that directly benefit us?

In our work and research, we’ve found that core values are often neglected or compromised due to day-to-day shifts in personal circumstances such as changing work or family commitments. As these priorities shift, each individual’s handling of their Choice Point becomes of ever greater consequence. When we have people rank their top core value, they rate their health above all else 99% of the time. Yes, above family, above relationships, above happiness, and always above world peace. We all know that to stay healthy, we need to exercise, eat the right nutrients, and stay hydrated. However, in 2021, the World Health Organization estimated that 2.8 million deaths were directly correlated to obesity. Many of those deaths could have been avoided. People know how to eat healthily, they know about hydration, and they know they should exercise. Yet many of us opt not to work out today because there’s always tomorrow. But today’s actions often result in us having the same thought, the same excuse, and the same lack of progress tomorrow.

If personal health is so important to us, why do we struggle to follow through with decisions that directly benefit us? This curious question is where our research starts: Why do some people opt in while others opt out?

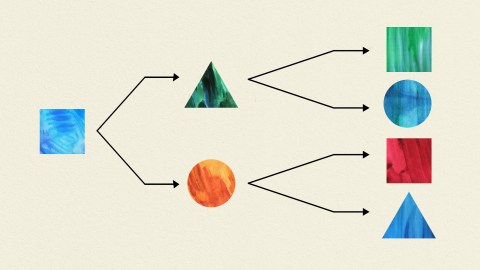

The answer is in your attention and imagination. One dramatic demonstration of how this works was revealed in the most significant weight loss study ever conducted without medication. Conducted by Linda Solbrig, PhD, and colleagues from the University of Plymouth, in Great Britain, and Queensland University of Technology, in Australia, it became the most widely read FIT (Functional Imagery Training) study published on weight loss. In the 2018 investigation, 121 participants were recruited from an ad placed in a local paper in Plymouth. They were split into two randomized groups. One group received motivational interviewing, an evidence-based, client-centered intervention that uses open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries. Motivational interviewing is the standard in “change talk” (a method that maneuvers people to discuss solutions and plans), and is used by teachers, doctors, coaches, therapists, and counselors in every field. The other group received FIT training and learned to use imagery to plan, anticipate obstacles, and try out new solutions based on past successes.

Solbrig worked with both groups over a period of six months and followed up after 12 months. The time investment to participate in the program was brief for both groups: Each participant received a single one-hour in-person session, one follow-up phone call (of 45 minutes or less), check-in calls (of 15 minutes or less) every two weeks for a period of three months, and then monthly check-in calls for three months. Each participant had just four hours of contact with Solbrig. The results were newsworthy and reported in media outlets around the world.

The FIT group lost an average of 9 pounds at the six-month mark, and most significantly, the results continued beyond the intervention. At 12 months, the FIT group had lost an average of 14 pounds, while the motivational interviewing group had lost only an average of 1.5 pounds. Despite not having received any support after the first six months, the FIT participants continued to make progress. Up until this study, this kind of outcome was unheard of in a weight-loss program. With just four hours of contact with the FIT practitioner in the first six months, and zero contact in the second half, the FIT group became self-sufficient and self-directed and the participants continued to progress toward their goals. It would appear that FIT gave them the confidence and the tools to persist.