Cosmism: The 19th-century movement to reach space and immortality

- Russian Cosmism was a philosophical movement that emerged in the late 19th century and aimed to redefine mankind’s relationship with technology and progress.

- Some Cosmists saw technology as destructive and transformative, while others believed its role should be to protect and preserve.

- Regardless of their differences, all Cosmists advocated for the attainment of immortality and colonization of outer space, goals people still strive for today.

In the 2009 documentary Transcendent Man, the American inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil shares his thoughts on death. Although many philosophers and theologians accept mortality as an inevitable and indeed defining feature of human existence, Kurzweil refuses to accept this line of thinking. “Death is a great tragedy, a profound loss,” he declares in the film, haunted by the memory of losing his father at age 22. “I don’t accept it.”

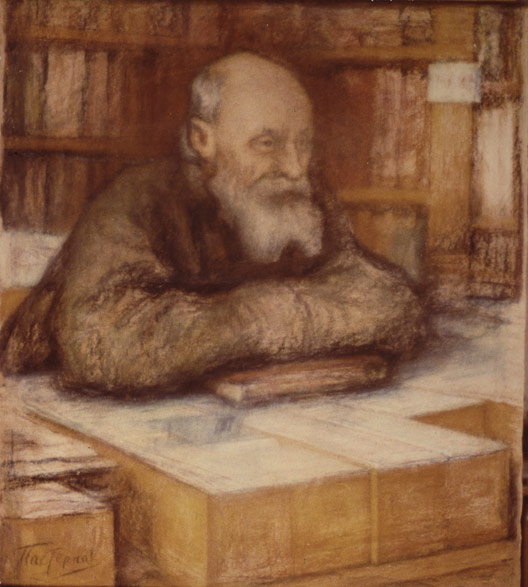

Kurzweil would have found an ally in the little-known 19th-century Russian philosopher Nikolai Fedorov, whose posthumously published text Philosophy of the Common Task made the at-the-time daring argument that death was little more than a design flaw — one which advancements in science and technology could help to rectify. Fedorov also believed that this goal of rectification — of achieving immortality — would unite social groups whose mutual fear of death had historically pitted them in opposition to each other.

“Our task,” Fedorov wrote, “is to make nature, the blind force of nature, into an instrument of universal resuscitation and to become a union of immortal beings.”

Fedorov’s writing never turned mainstream, but it did spawn a short-lived, visionary philosophical movement known as Cosmism. Materialized during the Industrial Revolution — a time of unprecedented societal change — the movement generally sought to redefine mankind’s relationship with technology and progress, with the ultimate goal of regulating the forces of nature so that humanity could achieve unity and immortality. The movement offered a more spiritual alternative to both futurism and communism.

Although the latter annihilated Cosmism before it had a chance to mature, its maxims have acquired new relevancy in the age of Big Tech. The following interview with Boris Groys, a distinguished professor of Russian and Slavic studies at New York University and editor of the new book Russian Cosmism, reveals why.

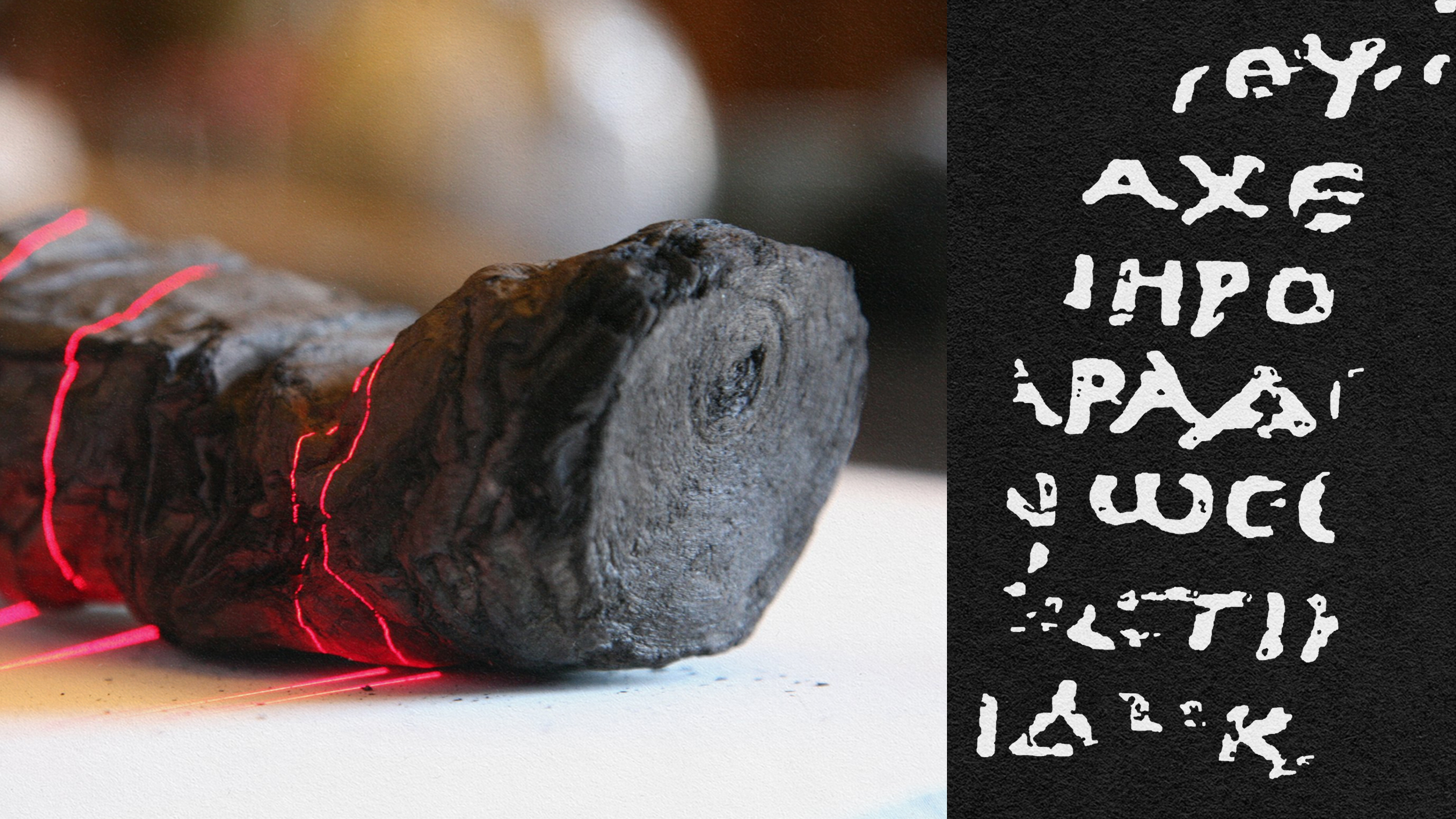

Into the crematorium

To understand Russian Cosmism, we must first look at other movements and ideas that arose during the same period. More influential than Fedorov’s Philosophy of the Common Task was interdisciplinary scientist Alexander Chizhevsky’s 1931 article “The Earth in the Sun’s Embrace,” which interpreted human history as revolving around the Sun. Starting from the questionable proposition that revolutionary movements require energy and that energy in its most basic form is derived from solar rays, Chizhevsky listed some historical developments that lined up with astronomical developments. He noted, for example, that progressive governments in the United Kingdom coincided with periods of high solar activity, while conservative ones tended to appear when solar activity decreased due to sunspots.

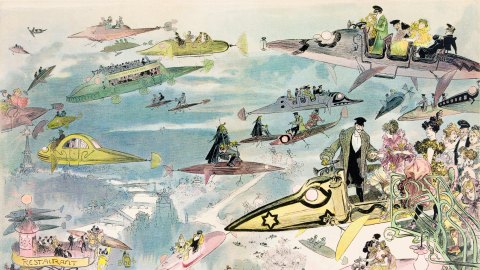

Chizhevsky’s article profoundly impacted Russian avant-garde artists like the painter Kazimir Malevich. Malevich helped stage a futuristic opera titled “Victory Over the Sun,” which heralded the Sun’s eventual extinction and the world’s descent into chaos. Rather than dreading this disorder, the avant-garde welcomed it. “By the beginning of the twentieth century the embrace of chaos seemed imminent, as no one could be expected to believe any longer in the stability of divine or natural order,” Groys explains in the new book.

“The very idea of a stable order, be it religious or rationalist, appeared to lose its ontological guarantee to permanently replace, make obsolete, and ultimately destroy old things, old traditions, and familiar ways of life, thus undermining lingering faith in the ‘traditional world order.’ Technological development, subjected to the logic of progress, presented itself as a force of chaos that would not tolerate any stable order. The future came to be seen as the enemy of both past and present. Precisely because of that view, the futurists celebrated the future, as it held the promise that everything that had been – and still was – would disappear.”

This same sentiment can be found in the writing of the anarchist-futurist poet Alexander Svyatogor, who compared progress to the sudden eruption of a volcano: a violent outburst that destroys everything in its wake while fertilizing the soil to sustain new life. In his essay “The Doctrine of the Fathers’ and Anarcho-Biocosmism,” he rejects Fedorov’s idea that science and technology are agents of restoration – of recovering and preserving what has been lost. He argued instead that future generations “would knead with their own hands, like sculptors knead clay, the spirit and matter of the world, so as to create an absolutely new cosmos.” Crucially, he also relished in the fact that detractors referred to his intellectual group — the “Kreatory” or “Creatorium” –—as a “crematorium.”

“They are probably right to come to this conclusion,” he wrote. “Indeed, we need to burn quite a lot, if not everything.”

Cosmism from Stalin to Musk

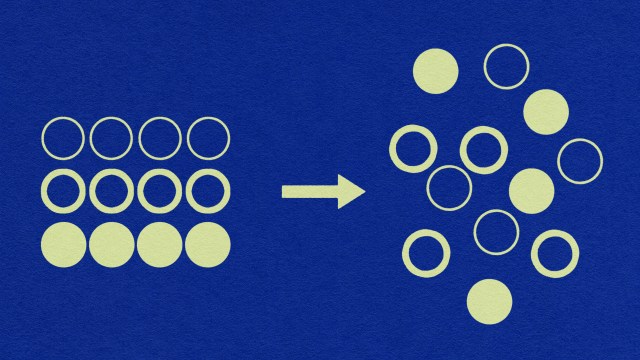

Fedorov and Svyatogor represent two sides of Cosmism, which Groys writes never had a unified doctrine. Where adherents of the former viewed technology as a “force that would destroy the ‘old world’ and open the way for building the new from point zero,” the latter hoped technology would become a “strong messianic force” that could transmit knowledge from one generation to another.

Cosmists who believed in technology as a messianic force clashed not just with the Svyatogor camp, but also with the communists, whose guiding ideology of Marxism-Leninism was predicated on the dismantling of age-old social systems to establish a novel world order. Fedorov’s philosophy was especially irreconcilable with the concept of the “New Soviet Man,” the Soviet government’s campaign to physically and mentally rebuild its citizens into more obedient, self-sacrificing people. While some Cosmists embraced communism, they opposed the notion that a socialist utopia should be built on the backs of generations who would never get to experience its benefits — commentary that put them at odds with Joseph Stalin and his purges.

Although interest in Russian Cosmism was quickly eradicated, the movement has acquired new life in the 21st century. In fact, it might be more relevant today than it was in the early 20th century. Fedorov and Svyatogor’s shared call for the colonization of outer space to protect humanity from earthly disaster, for example, is a direct parallel to Elon Musk’s promise to move people to Mars.

Thanks to climate change, Cosmism’s ambivalent and generally hostile attitude towards the natural world should also sound familiar. “Today it is fashionable to like nature,” Groys told Big Think, “but nature does not like us. It is a one-sided love. Cosmism’s central idea is that we can survive only under artificial conditions, if we create an artificial world to protect us.”

Fedorov’s writing, meanwhile, serves as a reminder that we should not let scientific or technological progress come at anyone’s expense, but rather strive to uplift the world in its totality: past, present, and future. “To be interested in the past is to be interested in ourselves,” Groys said, “because everything, including us, eventually becomes part of the past.”