Ancient Buddhist painting can help you understand the art of Zen

- Failing to find success in his native China, the monk Muqi became a huge sensation in Japan.

- Today, his serene and spontaneous compositions are widely seen as illustrative of Zen Buddhist ideas.

- A closer look reveals that this enticing interpretation of his work is not entirely accurate.

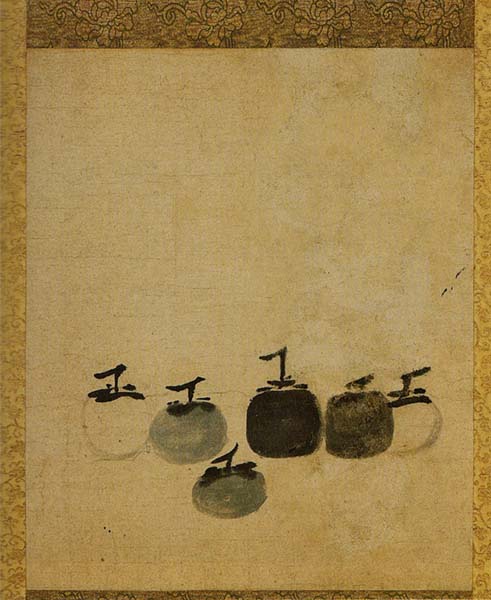

For months, conservators at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco were hard at work fashioning a display case for Six Persimmons, the 13th-century ink painting at the center of their upcoming exhibit, “The Heart of Zen.” Its owner, the Kyoto National Museum in Japan, had provided the conservators with an extensive list of requirements concerning not just the material and measurements of the case itself, but the quality of the air inside it.

Even to seasoned museum workers, the demands of the Kyoto team appear extreme, bordering on unreasonable. That is, until you consider the history of the art involved. Painted on a scroll by the famed Chinese monk Muqi, Six Persimmons is as fragile as it is coveted. For centuries, this minimalist still life of autumn fruit was owned by a wealthy Japanese family that only displayed it during their exclusive tea ceremonies. After ending up in the hands of Daitoku-ji, a Buddhist temple in Kyoto, it was moved to the National Museum — not to be displayed, but stored. “Heart of Zen” not only marks the first time Muqi’s masterpiece will be shown to the public since 2019, when it was exhibited at the Miho Museum, but also the first time it will be shown outside Japan.

The reasons for the painting’s coveted status are manifold. Although age and inaccessibility are part of the equation, those aspects pale in comparison to its status as a peerless illustration of Zen Buddhist philosophy. Created by an individual who is thought to have reached Enlightenment, Western and Japanese critics alike praise Six Persimmons for helping viewers find inner peace with its soft colors and quiet composition.

It’s an enticing and popular interpretation, and yet — as the San Francisco exhibit hopes to show — it may not be as historically accurate as many think.

The secrets of Zen Buddhism

Despite becoming one of the most famous Chinese painters of all time, Muqi struggled to find success in his home country. Born during the final days of the Southern Song dynasty, the monk’s idiosyncratic style — calligraphic renderings of mundane subjects like food, trees, and animals — clashed with the tastes of the Song, who preferred complex and representational art rich in worldly symbolism. The qualities that made Muqi an iconoclast in the eyes of fellow Chinese were received as forward-thinking in neighboring Japan, where his work would inspire painters for centuries.

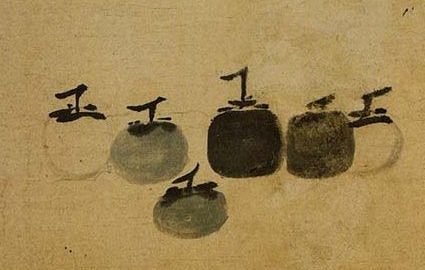

Glancing at Six Persimmons, it’s difficult not to think about Zen Buddhism. Born in China but cultivated in Japan, it rejects the study of ancient, esoteric scripture in favor of meditation. According to Zen Buddhists, Enlightenment was a product of unflinching introspection, not devotion to rites and rituals. By depicting a fruit that, in Chinese culture, was devoid of connotations, Six Persimmons forces the viewer to appreciate the subject for what it is, rather than the ideas it could represent. The result is a painting that cannot be analyzed, only experienced — the same way one interacts with rolling clouds or flowing water.

The persimmons, abstract in form and painted without shadows, float inside a depthless void. Yuki Morishima, an assistant curator at the Asian Art Museum who helped prepare the “Heart of Zen” exhibit and had been able to see Six Persimmons only once before in Japan, says she was as impressed with the painting’s negative space as she was with the positive space, with the actual persimmons. Her reaction evokes the Zen concept of groundlessness, which calls for the need to accept life’s inherent unpredictability.

If Muqi’s persimmons possess any symbolism, they are symbolic in the broadest sense of the word. The fruits themselves represent impermanence and the search for nirvana. Just as Enlightenment arrives after a lifetime of meditation, so do persimmons ripen in the fall, the season of death and decay. If preserved, their soft, sour flesh can be turned into a hard, sweet candy, mirroring the way a Zen Buddhist transforms suffering into serenity.

Six Persimmons: an aesthetic or a way of life?

A closer look at Muqi’s critical reception indicates that his current reputation as an enlightened artist is a misconception. Originally, Morishima tells Big Think, Six Persimmons was treated as little more than decoration. Its first owners, Japan’s Tsuda family, displayed it at their ceremonies not to prompt some kind of spiritual discussion, but because its subject matter matched the type of food they would have served their guests.

In a 2021 article from the Korean Journal of Art History, South Korean art historian Heeyeun Kang explains how Six Persimmons acquired its present-day significance. Arriving in Japan along with Zen Buddhism itself, Muqi only started to become recognized as an explicitly Buddhist painter when the Japanese elite decided to establish Zen as an explicit aspect of Japanese identity.

Spearheading this push for reidentification, Japanese critics like Okakura Tenshin, Aimi Kōu, and Awakawa Yasuichi likened Six Persimmons to the crucifixes found inside Christian churches — icons that seek to convey through visuals what the New Testament expresses with words. When Zen Buddhism started gaining popularity in the West, a popularity that endures to this day, European and American writers accepted this new and highly marketable interpretation of Muqi’s work without a second thought.

Although Six Persimmons may not be the intentional Buddhist masterpiece many believe it is, this doesn’t mean the painting is any less impressive as a work of art. An optical counterpart to poetry, Muqi’s simplistic brushwork evokes emotions that are anything but simple. Standing in front of the scroll has a similar effect as meditating or opening the Calm app on your smartphone.

The longer you look, the more the struggles and anxieties of ordinary life begin to fade away, leaving only beauty, contentment, and a strong awareness of being. Just being.