How three students wrote history by winning the Vesuvius Challenge

- The Vesuvius Challenge has handed out its $700,000 grand prize.

- The winners, three students, deciphered ancient texts that have not been read in millennia.

- Moving forward, the challenge hopes to read many other damaged documents.

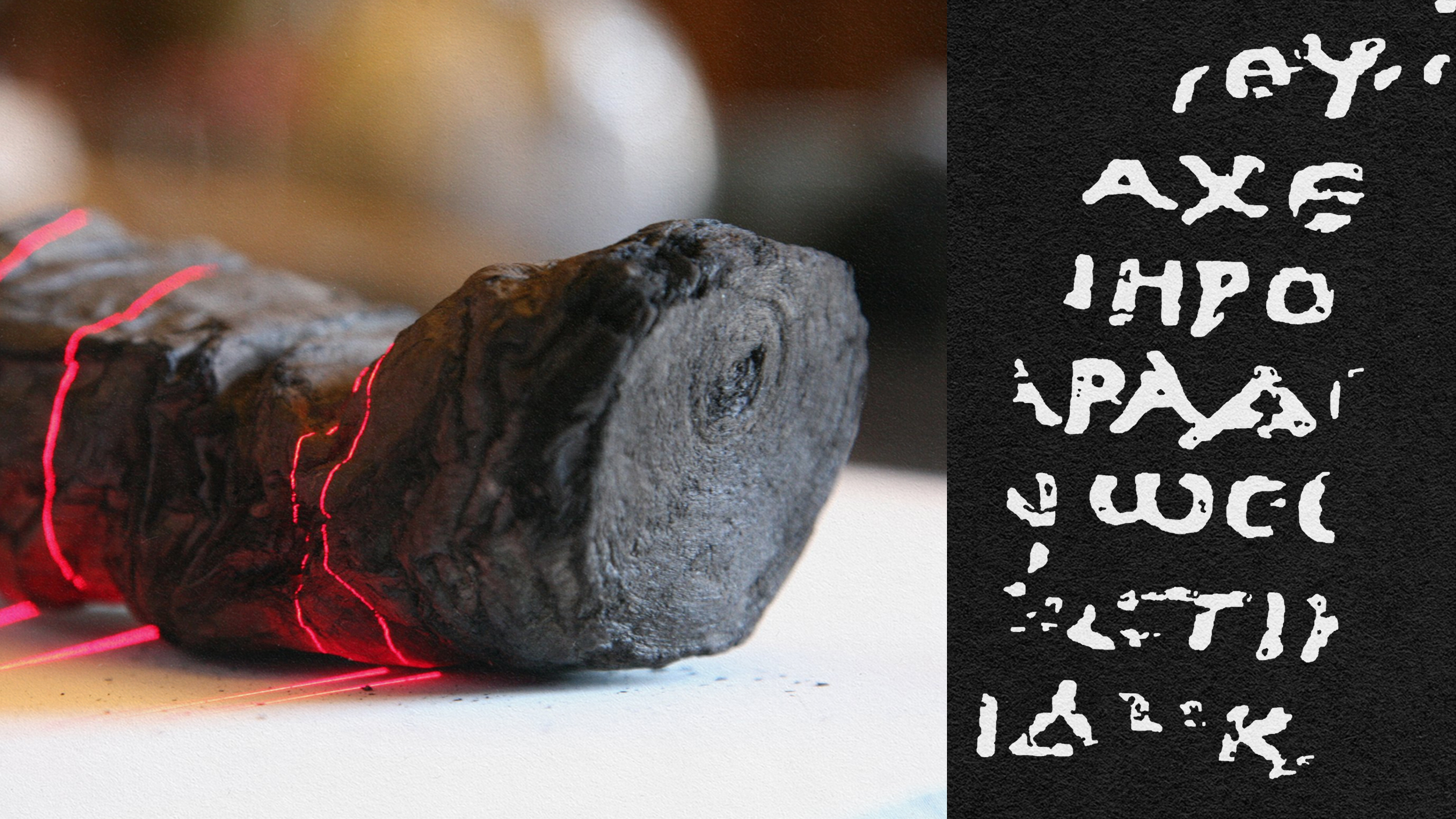

For nearly 20 years, a computer science professor at the University of Kentucky named Brent Seales tried to develop software to pry open ancient scrolls that were charred and buried during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. Eventually it became clear to him that the work was too much for a single team, so he considered making use of rapid advances in the field of AI. He then had another, even bolder idea: to turn the project into a worldwide, open-source contest.

Combined, these ideas fueled a breakthrough. Since its March 2023 launch, the Vesuvius Challenge – funded by technology investors Nat Friedman (former CEO of Github) and entrepreneur Daniel Gross, among others – has made more progress toward unwrapping and reading the scrolls than anyone could have imagined. Machine learning automated processes that would have taken human beings decades to complete, while the competition generated a multinational network of bright minds that worked together rather than against each other.

Talent often comes from unexpected places, and the Vesuvius Challenge was no exception. The winners of its coveted Grand Prize – a whopping $700,000 awarded on February 5 – weren’t distinguished professors from prestigious universities, but three promising young students, one of whom is still an undergraduate. Here’s how they did it.

The unrolling problem

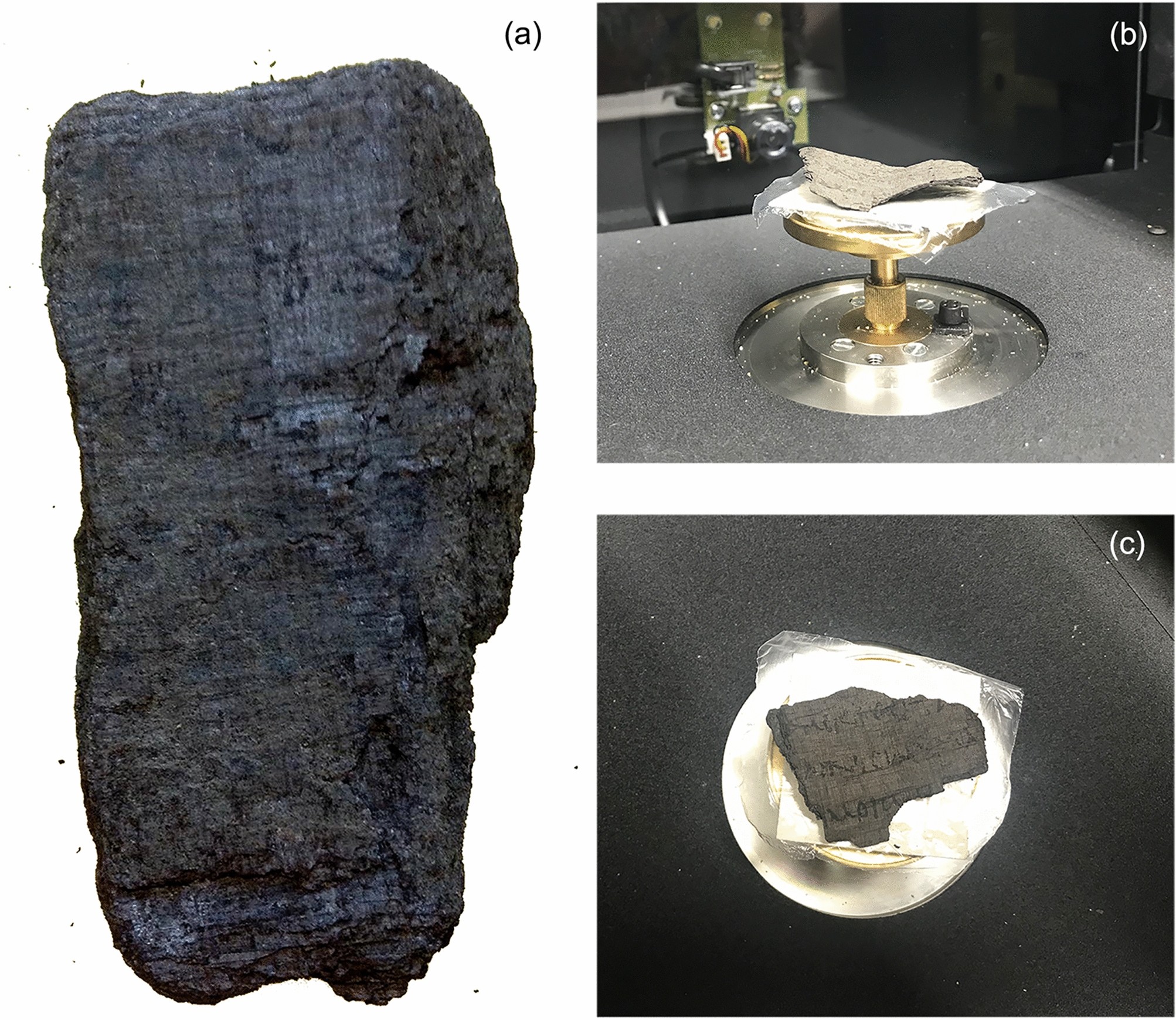

Julian Schilliger learned about the Vesuvius Challenge the month it was announced. Drawing on what he learned studying data science at the Freie Universität Berlin and building humanoid robots in his spare time, he threw himself onto the competition’s first and arguably most time-consuming problem: segmentation. In Vesuvius-lingo, segmentation means creating code that can digitally unroll CT scans of the scrolls, which are too brittle to be handled physically, in turn allowing artificial intelligence to look for faint patterns of ink on the blackened surface.

“It’s a computer vision problem,” he tells Freethink. “The rolled-up papyrus scrolls are difficult to read, let alone extract. My software enhanced an already existing tool developed by EduceLab called Volume Cartographer, enabling it to go from small 2 millimeter segments to close to 3,000 square centimeters – improving sheet extraction 10,000 fold!”

Although Schilliger had already won some of the challenge’s smaller prizes, this breakthrough helped put him in touch with Youssef Nader and Luke Farritor, whose work on ink detection had revealed the first legible words in the competition and earned them the sought-after $40,000 First Letters Prize back in October. “To them, it was clear,” Schilliger reflects. “Solving the segmentation problem was one of the Grand Prize requirements, and so they wanted me on their team.”

Working alongside Nader and Farritor, Schilliger developed ThaumatoAnakalyptor, a fully automated segmentation tool that can digitally unroll the scrolls without actually unrolling them. “It works by extracting surface points from the CT scan and grouping the points to sheets,” Schilliger explains. “The sheets are translated into a mesh using a Poisson surface reconstruction, which can then be used to texture an unrolled representation.”

Thanks to ThaumatoAnakalyptor, Nader and Farritor now had a large, flat surface area to work with. This was great news considering that, for the Grand Prize, they had to recover not words but sentences: 4 passages of 140 characters each, to be exact.

Searching for ink

The ink detection side of the competition posed huge problems, too. “Since the ink and the papyrus are both made of carbon, they have similar appearances in X-ray, so it isn’t easy to see the ink in the scans,” explains Stephen Parsons, a visiting scholar from the UK Digital Restoration Initiative and research advisor on the Vesuvius Challenge. “In some cases, the ink is thick enough that its texture can be observed directly, which resembles peeling paint or cracked mud. These can be labeled, indicating to an algorithm that they are ink. Algorithms can be trained and used to detect where else ink may be. By iteratively taking these predictions and cleaning them up, and training algorithms again, gradually they learn to detect more subtle traces. When it is applied to a section of the scroll, it will unveil the text.”

The biggest obstacle, Nader tells Freethink, “was how to get more letters. There were areas that were completely dark and we were trying to figure out why letters were not showing up there. Our conclusion was that perhaps the letters weren’t lost in the segmentation, but that the ink models needed to be improved. I spent a lot of time making stronger models to squeeze those letters out, and finally we were able to satisfy the winning condition of 85% readability.”

For Nader, winning the First Letters Prize made him feel both optimistic and cautious. “I was afraid,” he says, “because I knew I had the best model and was ahead, but the community of this challenge was knowledgeable, and in time others would catch up, which took only a couple of weeks. 85% was a hard target, and slowed the progress. Still, having worked on the first letters, I had an instinct of how to push forward. Throughout October, November, December, the process of us succeeding was quite fluctuating. In the end, though, we won not only by time, but also by being the only team to reach the winning conditions.”

At the end of its first year, the Vesuvius Challenge has managed to decipher 5% of one ancient scroll, resurrecting text that has not been read for millennia: “In the case of food, we do not right away believe things that are scarce to be absolutely more pleasant than those which are abundant,” one line reads. “…for we do [not] refrain from questioning some things, but understanding/remembering others,” another goes. “And may it be evident to us to say true things, as they might have often appeared evident!”

Robert Fowler, an emeritus professor of Greek at the University of Bristol who analyzed the text, believes it to be a copy of a work of Philodemus, a student of the famed Athenian philosopher Epicurus – a conclusion he had reached as early as the announcement of the First Letters Prize.

Vesuvius 2024

The Vesuvius Challenge is not over. On the contrary, it’s just getting started, with 2024 bringing more ambitious assignments and bigger rewards. The 2024 Grand Prize will go to the first team which manages to decipher no less than 90% of a text – an achievement which will net them a total of $100,000. The challenge’s organizers hope that, with this milestone, AI will be able to read all 1,800 scrolls that have been recovered from the ruins near Vesuvius, and possibly thousands more yet to be uncovered — not to mention other ancient, fragile documents such as some of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Although many were stunned by the challenge’s success, Seales had actually seen it coming. “I may have been the lone voice predicting the chance of success at 90% or near certainty,” he admits. “But the scientific basis for my expectations was clear before we initiated the contest. I believed it was a matter of time and acceleration, which is exactly what the competition provided.”

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.